It Is Good That You Exist

Finding hope in the midst of suicide ideation

This piece reflects on childhood abuse, abandonment, and suicidal ideation. If these themes are tender for you, please take care as you read.

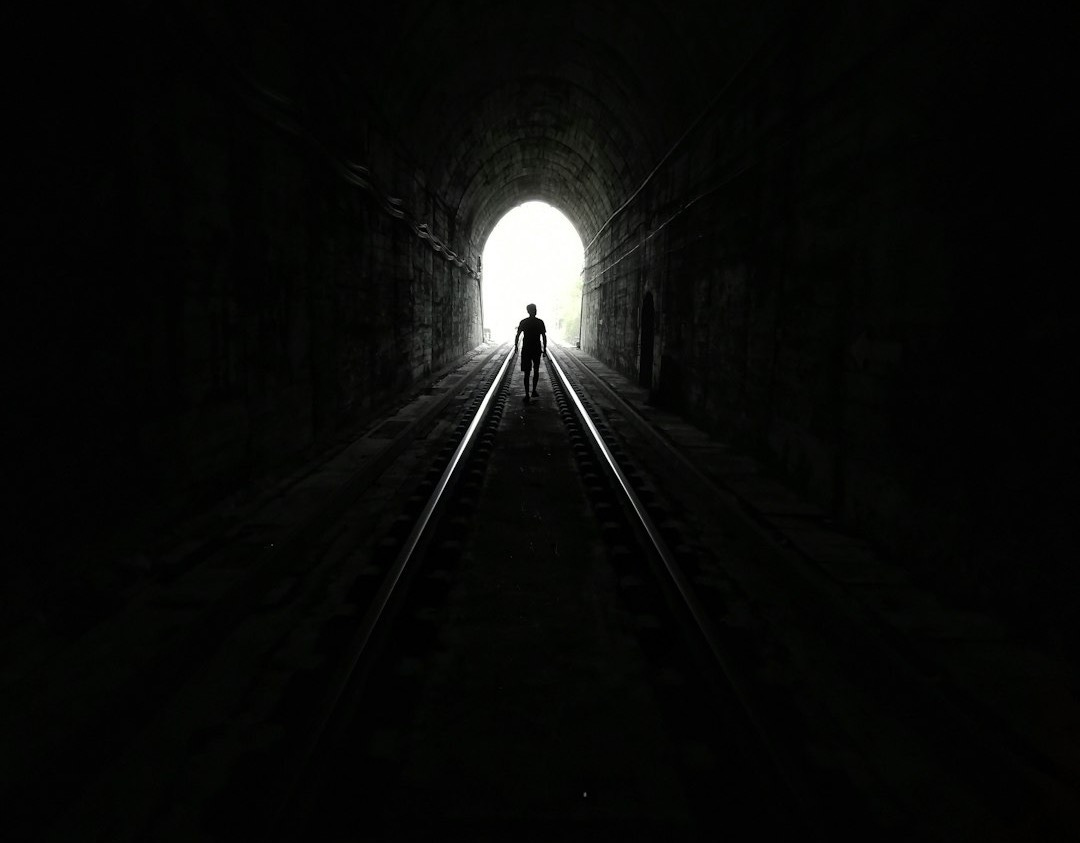

I’ve known the quiet seduction of the siren song — the pull toward not being here anymore. Not dramatically or impulsively, but as a slow ache: a longing to be unmade, so that the overwhelm and pain might finally cease. To lay it all down. The weight of abuse, abandonment, and the care I was supposed to receive as a child but never did took up residence in my soul. And the older I became, the more life seemed to expose that absence.

With every new responsibility, every relationship, every expectation, the lack grew louder. The demands of adulthood — work, calling, even faith — revealed the hollowness in me. Not as fresh wounds, but as old ones that had never healed, because there was never anything there to begin with. That emptiness, once unquantifiable, became painfully visible. Measured. Known. And eventually, life began to feel like a mountain with no summit — a climb I was never equipped to make.

Anxiety and depression became the atmosphere I lived in — subtle at times, suffocating at others. My prayers thinned into silence. My hope flickered dangerously close to extinction. And in that desolation, death didn’t feel like rebellion. It felt like rest. Like sabbath. Like the only open door I might choose.

“I have often been so depressed that I could not even pray. I wanted to die.”

— Henri Nouwen, The Inner Voice of Love

Beneath all of it — even beneath the longing for death as escape — was something deeper: a cry for deliverance. A desperate yearning to be rescued from the chaos planted in me when I was still a child. To be met by Someone who could see the whole story of my life and say, It will all be okay. What I mistook for a desire to end was, at its core, a longing to know my end — and to be carried there, not alone, but with love and mercy.

The psalmist says, “If I make my bed in Sheol, you are there.” And I did. Depression and anxiety led me into the shadowlands — the space between what is and what I wished was. A place where sorrow hangs heavy, and rescue and resolution feel far away. In those shadowlands, suicidal ideation became a kind of siren song — promising relief, an end to the ache, a way out when nothing else seemed possible.

“The mind can descend far lower than the body, for there are bottomless pits.”

— Charles Spurgeon

I have known those depths — the kind that swallow words, faith, and hope. My life felt like it was always winter: frozen in grief, heavy with silence, untouched by a spring that never came. And yet, even there, I can now see that another song was already sounding.

As a child, caught in the chaos of abuse and absence, I was drawn to Aslan — to the hope of a Lion who rescues, who speaks peace into fear, who ends the long winter. I see now that my moments of longing to die were really a longing to be delivered. What I needed was not escape, but rescue. And it is Aslan’s voice — steady, wild, and full of kindness — that has called me out of the shadowlands and back into life.

“You never know how much you really believe anything until its truth or falsehood becomes a matter of life and death to you.”

— C. S. Lewis, A Grief Observed

And maybe that is what faith is — not the absence of sorrow, nor even the absence of the desire for death itself.

You Are Not Alone

As a pastor for over twenty-five years, I spent thousands of hours listening to people share their trials — and the toll those experiences had taken on their hearts, minds, and souls. Over time, I began to notice a quiet refrain, spoken in different ways but echoing the same pain. Often it came with hesitation, preceded by the confession that they had never told anyone this before. Then the words would follow:

“I just want to go to sleep and never wake up.”

“I wish I had never been born.”

“I’ve thought about ending it all.”

“No one would miss me if I were gone.”

“My family would be better off without me.”

“I’ve been thinking of ways to end my life.”

These were not rare admissions — they were heartbreakingly common.

Suicidal thoughts often arise from a desire to escape pain, not necessarily from a desire to die. They are frequently hidden; most people who struggle with them do not share them, even with close friends or family. One of the simplest ways I learned to bring relief was by letting people know they were not alone — and that they were in good company, mine included.

Suicidal thoughts are far more common than we tend to admit. They are not limited to those with visibly tragic lives. Even people of deep faith, strength, and apparent stability can find themselves in that dark place. Around one in five people will experience a mental health illness in their lifetime, and suicidal ideation is a common companion to many of them.

And I suggest suicidal thoughts are a normal dimension to faith, not an aberration of it.

Suicidal Ideation and Faith

The Church must learn to be a place where the cross is not just preached but shared — where suffering isn’t explained away but held with reverence. Suicidal ideation is not always about wanting to die — it’s often about not knowing how to keep living. These moments, as dark and terrifying as they are, can be a kind of participation in the mystery of the cross.

When someone says, “I can’t do this anymore,” they may be closer to the cross than they know.

To be a Christian is to be one who has come to the end.

— Fleming Rutledge

The Scriptures are full of those who came to that edge. Job cursed the day of his birth. Elijah begged for death beneath a tree. Jonah, Jeremiah, and even Paul. And Jesus Himself — on the cross, in the dark — cried out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

The cross is the point at which God says, ‘Me too.’

— John Stott

That cry was not weakness. It was participation. And when we find ourselves in places of despair, where death seems like the only relief, we are not stepping away from faith — we may be entering the very heart of it. Suicidal ideation is not a sign of faith lost, but of suffering felt — a form of communion with the Crucified. The dark side of the cross is not failure, but the place where love bears unbearable weight.

God is not found in the way we think strength looks. He is found in weakness, in vulnerability, in the crucified Christ.

— Jürgen Moltmann

This is a theology that doesn’t fix suffering but walks with it. Like Jesus on the road to Emmaus, God often meets us in our despair, unrecognised at first, walking beside us in our unspoken grief.

The mystics and Church Fathers knew this terrain well. St. John of the Cross wrote of the dark night of the soul — not as punishment, but as purification. A place where all false comforts are stripped away, and we are left with the raw presence of God.

Christ passed through every stage of our suffering so that He might be with us in every moment of ours.

— Gregory Nazianzus

The Church’s role is not to rush people out of that place, but to remain with them in it. Like the women at the foot of the cross, we are called to stand near — not to offer answers, but to bear witness to their pain. To hold space for lament. To walk with those who can no longer walk alone.

We should also guide them toward help—therapy, medication, community—as gifts of God’s grace, not sources of shame for struggling to cope. The cross is not meant to be carried alone but to be shared.

There is no pit so deep that He is not deeper still.

— Corrie ten Boom

What if, instead of seeing suicidal ideation as a departure from faith, we saw it as an invitation? Not an invitation to death but to meet Christ in death’s shadow, to be drawn into His suffering, and by grace to be drawn out again.

God is not absent in our despair, but present in it.

— Rowan Williams

This is not the spiritualising of pain, but is the sanctifying of it. Saying: You are not alone. You are not broken beyond repair. You are wanted and held. And the voice of Jesus calling you out of the darkness does not shame or accuse. It’s the voice of the Good Shepherd — calling you by name, reminding you: This moment and overwhelm is not the end of your story.

The Cross of Approbation

Jesus has kindly invited me into — and patiently guided me through — many experiences of his cross:

The cross that saves

The cross that I share

The cross that I choose

The cross that heals and restores

Each has brought real transformation and real respite from the desire for death. And yet, another dimension has come into view.

The cross of approbation.

Approbation is when someone with authority openly says; This is good. This is accepted. This belongs

This is the cross where my Christian life — and even moments of suicidal ideation — are no longer something merely to endure or manage, but are drawn into a deeper and more radical truth: even here, I belong. Even now, I am wanted. The cross of approbation is where God says Yes to a human life - my life - at its lowest point

The resurrection does not correct the suffering of the cross; it confirms it. Easter is God’s approbation of a life fully lived in trust and self-giving. The Father’s Yes is spoken over the Son — not because the suffering was good, but because the Son was.

If God can say Yes to his broken, bleeding, abandoned son on a cross, then my life is not disqualified by pain, weakness, or despair. This does not glorify suffering, nor does it say pain is good.

Instead, it says: My being is good — even when I and if life feels unbearable.

God’s Yes, HIs blessing, comes before my healing, before my strength, before my usefulness, before my understanding. It is an ontological blessing — a blessing spoken over my being itself.

I do not earn this, yes. I do not prove my way into it. I do not lose it when I fall apart. I receive it before I do anything right, I believe correctly, or I am healed or whole.

Because: It is good that I am here.

“If an individual is to accept himself, someone must say to him: ‘It is good that you exist.’”

— Joseph Ratzinger

The abuse and abandonment of my parents carved a void within me — a hollow where the most basic affirmation of identity should have taken root. Instead of It is good that you exist, I absorbed something closer to: your existence is about me and my needs.

Suicidal ideation often lives in our voids. It is not dramatic or impulsive; it is the grim logic of a soul never told enough that it was good to be. As my life’s demands increased, childhood absence became more visible, and the void began to ask whether it might finally be filled by ending life.

But here, at the cross, there is an inversion by God.

God does not look past the void to find a more acceptable version of me. He looks directly into it — into the exact centre of that hollow place — and affirms even that.

Instead of disappearing, I am invited to enter the tomb with Christ. I bring the void — the wish not to be — and place it where it belongs: inside his death. Christ carries it all the way down and leaves it there. What rises is not an improved version of me, but a resurrected one.

This is an Easter exchange.

In Practice

If the desire to disappear returns, I will not argue with it or shame it. I will offer it to the Lord. I will name it as participation, not failure: “This, too, I give you to you.” I will choose to die with Christ, rather than without him. I will let the Father’s Yes to my existence be my truth.

It is good that I exist.

And it is so very good that you do too.

Thanks for sharing Jason. I especially loved this paragraph as I sit here in Minnesota just tired and drained right now..."The Church’s role is not to rush people out of that place, but to remain with them in it. Like the women at the foot of the cross, we are called to stand near — not to offer answers, but to bear witness to their pain. To hold space for lament. To walk with those who can no longer walk alone."

Finally have enough breathing room to go back and read this. So glad I did. Thank you for giving voice to the pain and giving a path through it, with Jesus.