Why Not Become Fire?

Is it time for holiness to make a comeback?

Our relationships with others are the measure of life—not how much I have earned, owned, or experienced, but how much I have loved and been loved.

Upon death, we realise and crystallise the underlying investments of life - the portfolios of our hearts, minds and souls vested in our relationships. The wealthy celebrity who dies isolated from others in a large house, surrounded by trophies and awards from yesteryear, seems impoverished. The great leader who accomplished many things has their legacy brought low when revelations come to light about the poverty of their parenting. No amount of success, fame, and fortune can replace being loved and loving others.

Yet, we often trade away the relational richness of life and mortgage our futures into isolation, believing that when we have more time and resources, we will invest in what we all know to be the more profound, essential, and abiding dimensions of life.

This is the enemy's lie and our self-deception—that we will buy into the eternal when we have more of what will not last for eternity.

Our self-deceptive ways of life are autocatalytic and nurture the very things we want less of. We go away to escape life and feel worse. So we go away more and more. We are just one more time away from feeling at peace in the life we are escaping. We are tired, so we avoid being with people. Being isolated from others makes us more tired, so we avoid people even more.

The truth is that no matter what and how much we lack - health, finances, relationships - being loved, loving others, and knowing God's love is available to us right now, not later. This reality is closer than the air or our next breath, our next thought, next feeling, and next moment of overwhelm. As Jesus said, if we put such eternal things first, all other things will be added unto us (Matthew 6:33).

In the Gospels, Christ ministered to the poorest, who lacked everything. He did not take up arms to set them free from their oppressors. He did not hand out fish and bread every day. Instead, he opened heaven over them, making available the most astonishing riches—the experience of loving God and loving others. From this, the transformation of life and the whole world flows.

Which brings us to holiness.

The Failure of Holiness

Christians have long known that the more we have in life, the less it seems we have, and the more likely we are to procrastinate on investing in things that bring us eternal life.

Our world has changed so rapidly. In two hundred years, we have gone from a life expectancy of forty years to eighty. Where life was short and brutal for most people, the possibility of a long life for many and inheritances to pass on became the norm. Christians were suspicious of this sudden change of affairs, primed as they were with a suspicion of prosperity throughout Christian history.

In response, the Holiness movement, principally through Methodism, Quakers and Anabaptists, came into being. Like all movements, the Holiness movement was complex and multifaceted but consciously focused on sin and sanctification as resistance to the world's distractions. At its best, the Holiness movement was about how loving God and others required attention to the lure of ever-increasing material provision.

Whilst correct in many of its prognostications, the Holiness movement collapsed under the weight of its byzantine theological constructions for sanctification. However, its demise was primarily due to its austere and suffocating cultural ascetics. In short, it created a spirituality of judgmentalism, shaming, and pretence. Pharisaical self-righteousness led to a spiritual death of hearts and souls and a breeding ground for secret sins, including those of senior leaders hoisted by their own Holiness petards.

I was once part of a short-lived attempt at a revival of holiness in my early twenties. The premise was that we must clean up our act if we want more of God's presence. What I remember was not more of God in my life but a focus on policing what I said and watched and fearing about anyone knowing my sins. The most interesting leaders were the ones who broke out the whiskey, played cards, and smoked cigars after a church meeting.

Holiness movements died out and were replaced with more materially benevolent forms of Christian spirituality that embraced the idea of a God who provides for us in return for holding correct beliefs and observing a few Christian behaviours. Sin became limited in the scope of any accounting for and focus upon. Ultimately, we ended up with a form of Christianity where faith is about getting a material way of life that everyone else is also pursuing. God is reduced to a means to another end, a way of life we aspire to and expect from Him.

The pursuit of material things has indeed corrupted us. If we are honest, many of us would trade away being closer to God and others for a better job, home, and location. Indeed, we have already done so in practice.

Such spiritualities guarantee that the eternal is secondary to us and ensure the death of any legacy of faith in our lives. We enter death with most of what might have been unrealised and unexperienced, and a truncated spiritual legacy.

Our world is in turmoil, and the habit and instinct around our addictions for the non-eternal is kicking in hard. Every developing anxiety about ways of life that seem more at risk is an opportunity to notice something. Instead of doubling down and delaying our investment in the eternal, we might sit with Jesus, listen to his advice, and take hold of his remedy.

31 Therefore do not be anxious, saying, 'What shall we eat?' or 'What shall we drink?' or 'What shall we wear?' 32 For the Gentiles seek after all these things, and your heavenly Father knows that you need them all. 33 But seek first the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be added to you.

- Matthew 6

Whatever assails us, has hold of us, and grips us - the intensity and suffocation of it all - is nothing compared to what Christ has for us right here and now, as he offers to take hold of and possess us instead.

The Return of Holiness

This is where holiness might make a needed comeback, but a more ancient and life-giving kind. One that helps us navigate where our hearts are not set on the eternal. But how will we avoid falling back into the pitfalls of Holiness movements? By refocusing on what holiness was meant to be about in the first place. Holiness is about what our hearts and minds are given over to and owned by.

There is a growing desire for a spirituality in which faith is no longer a means to a material end. The realisation that our desire for the things of the world has replaced a desire for an experience of God and others, to pause and notice what our hearts and minds have been given to instead of God.

And this is where true holiness starts—with desire.

The Holiness movement became a psychology of suppression—the bottling up of desire, anger, sadness, and disappointment into policed behaviours. Such supression gets acted out into sterilised passive-aggressive behaviours and judgmentalism. Cognitive dissonance provides a pressure valve for release into secret sin.

Instead, holiness should be the psychology of humans flourishing around desire. St. Ignatius predates the discipline of psychology, but his spirituality and spiritual exercises are deeply person-centred and offer an alignment around the best psychological well-being and holiness.

Ignatian spirituality is about exploring how our desires give rise to our attachments. And how those attachment might get in the way of our desire for God and our relationship to Him. Our deepest desires and attachments, no matter how broken and damaging, reflect something we want from God. By noticing and being honest with God about our desires and attachments, we can find the freedom and connection to Him we long for.

There is no cover-up, hiding, or pretending - everything, even sin, can show us the way to the God who loves us.

This Ignatian spirituality has practices and dispositions, not as the policing of desire but for the expression and re-ordering of desire, and include:

God in all things: God can be noticed and present to us in all life. All of our life experiences are places to discover God. We do not have to clean our lives up to find God, for he is already present in the messiness of real life.

Ignatian Indifference: This is not a lack of care but instead is about developing the capacity to let go of things that hinder us from loving God and others, take hold of what brings us greater spiritual freedom, and discover who God made us to be.

Gratitude: Where our disordered desires and attachments are usually formed through fear of lack, Ignatian gratitude helps us see and experience God's present generosity. This allows us to become generous in return with what we otherwise hold onto in fear of lack.

Authenticity: Honesty is a core principle in Ignatian spirituality. It emphasises living authentically and truthfully, embracing the good and the willingness to challenge all aspects of our lives. In Ignatian prayer, we talk openly with our heavenly Father, being vulnerable and honest with Him about our soul and its movements. We also share with other trusted friends who are making the same journey with God, free from fear of judgment and shame (and here, a spiritual director can be a great help).

Recapitulation: We explore the story we are living by and what that produces in our lives, comparing it to what a life lived in Christ and his purposes for us might be instead. We discover things that need to die in us so that resurrection might come to us now and not just at the end of our lives.

In short, Ignatian spirituality offers an understanding of ourselves in relationships with God that naturally leads to holiness. Here, our desires and attachments become those God has for us. Our character, disposition, and nature become more like the person God meant us to be, where we are free, at peace, and filled with love for God and others.

Inflamed with Love

I call it consolation when an interior movement is aroused in the soul, by which it is inflamed with love of its Creator and Lord, and as a consequence, can love no creature on the face of the earth for its own sake, but only in the Creator of them all. It is likewise consolation when one sheds tears that move to the love of God, whether it be because of sorrow for sins, or because of the sufferings of Christ our Lord, or for any other reason that is immediately directed to the praise and service of God. Finally, I call consolation every increase of faith, hope, and love, and all interior joy that invites and attracts to what is heavenly and to the salvation of one's soul by filling it with peace and quiet in its Creator and Lord.

- The Spiritual Exercises, #316

Ignatius describes how moments can come to us as we explore our relationship with God in the abovementioned ways. We find peace, hope, joy, and love in the deepest parts of who we are, which we have always longed for, and where our love for God can be like a consuming flame.

Holiness is not about achieving a flawless perfection that separates us from the messy realities of the world, but rather about surrendering ever more deeply to the embrace of a God who meets us precisely in our brokenness, transforming our vulnerabilities into sacred spaces of encounter.

When I undertook the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises, I was unaware of annotation #316 above and yet had the experience it mentions. I had spent several months praying through the gospel stories about Jesus, expressing my deepest fears and losses, and being honest with God in the ways Ignatius directs. The Lord would often graciously ask if we could revisit moments in my life, painful ones, and my responses to them. There was no condemnation or judgment, just love and revelation. And from that sometimes flowed repentance as an expression of my gratitude to God.

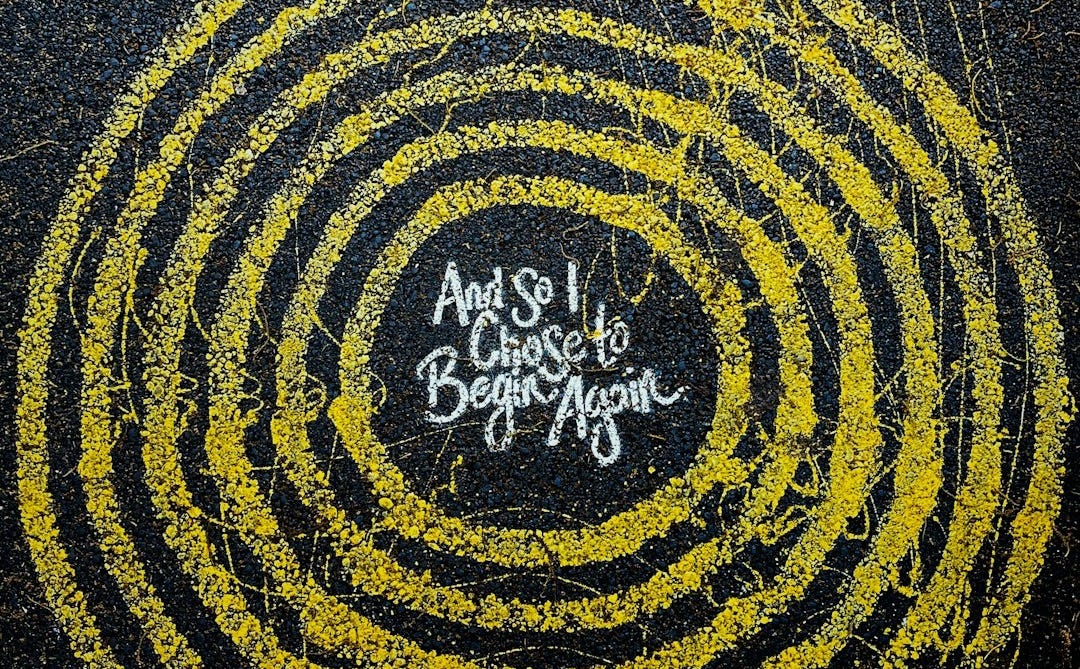

And something began to grow in me.

I wanted the Lord more and more. And I wanted Him more than my fears, anxieties, and ways of controlling my inner life less and less. When telling friends what God was doing in me, I struggled for words and described it like a fire burning within me. I found a new level of freedom and a change in my inner life.

I dare to use the word holiness to describe my experience. I have experienced God's holiness and its impact upon me. I am holier than I was—not in a pious, self-righteous way, but in an Ignatian way, of feeling and being possessed by Jesus. Set apart from other things into a new freedom to choose Him. My appetites have changed, and my desire, and freedom to return myself to him in love have increased.

My wife tells me she sees more love, joy, peace, kindness, faithfulness, and self-control in me. This may be holiness. And if so, it is a kind I aspire to more of, after having been wary of the word for so long.

Holiness: Why not become fire?

A story from the desert fathers:

Abba Lot came to Abba Joseph and said:

Father, according as I am able, I keep my little rule, and my little fast, my prayer, meditation and contemplative silence; and, according as I am able, I strive to cleanse my heart of thoughts: now what more should I do?

The elder rose up in reply and stretched out his hands to heaven, and his fingers became like ten lamps of fire. He said:

Why not become fire?

I needed to read this today