You're Not Just Traumatised, You're Also a Sinner

And admitting that might actually set you free

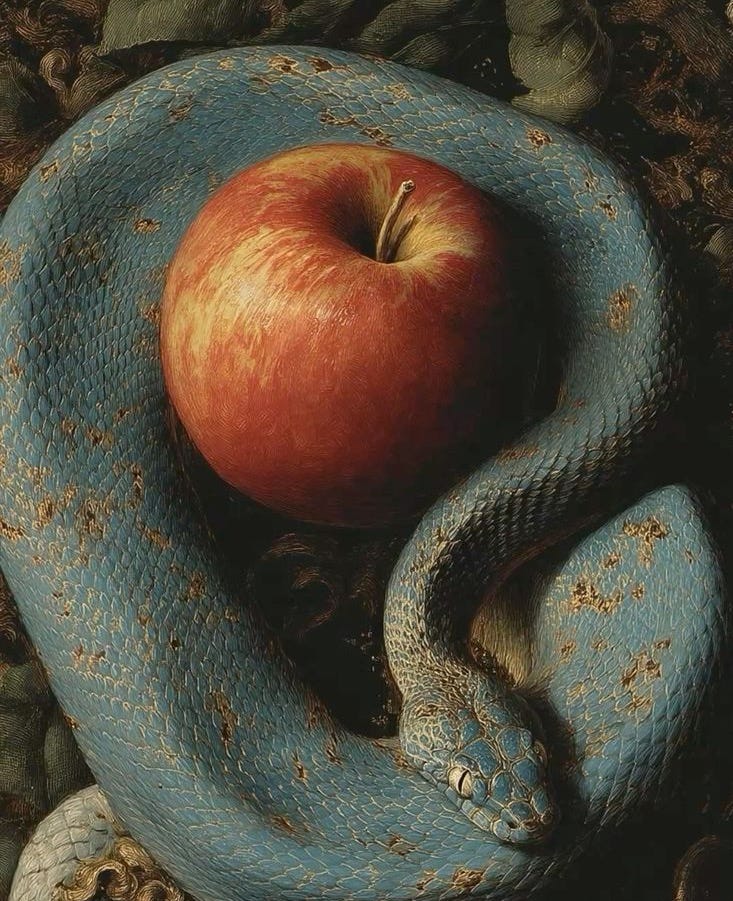

We have become a culture obsessed with trauma and deeply allergic to sin.

Even in evangelical churches—once the strongholds of sin-consciousness, altar calls, and conviction—the language has shifted. We now speak easily of healing our wounds, processing our pain, and understanding our trauma. We are shaped by our upbringing, our circumstances, and our neural pathways. We are victims of forces beyond our control.

We are rarely, it seems, sinners.

This isn’t entirely wrong. But it is dangerously incomplete.

When we refuse to face our own sin, our sense of agency becomes fragile. We no longer know where responsibility properly lies. As a result, even other people’s perceptions and thoughts begin to feel dangerous. To be interpreted, criticised, or even misunderstood is experienced not as a normal part of being human, but as an act of reduction and diminishment of who I am.

Blaming others for how they think about us is a warning light on the dashboard of our souls. What feels protective actually deepens our captivity. It hands our inner stability over to the judgment of others.

Facing sin interrupts this. When responsibility for our lives is owned in the presence of God’s grace, our identity no longer hangs in the balance of how others perceive us. We can be seen without being undone. Some judgments may indeed be wrong, some may be true, but neither has the power to define us. But only if we consider ourselves as sinners who sin.

We have tried to build psychological health without moral responsibility—healing without culpability, freedom without repentance. The result is a dangerous return to shame without forgiveness. In shame cultures, we can be exposed, cancelled, and labelled, but never redeemed.

A Christianity that forgets sin cannot sustain grace at all. When sin is removed, grace no longer has anything to do. It collapses into a kind of sentiment of kindness without cost, mercy without transformation, and love without truth. The cross is also reduced to a therapeutic tool, a symbol of reassurance rather than of redemption. Resurrection becomes little more than an affirmation of God's validation of us as we are, rather than a raising and resurrection into a new kind of life.

In the psychological turn, to be “saved” means feeling seen, soothed, and affirmed. These are important, but they are not salvation. Salvation is deliverance from sin’s power, from disordered desire, from the patterns that keep us bound, and ultimately from death itself. When our faith can no longer name or address these realities, it may comfort us, but it can no longer save us from what actually destroys us.

Trauma Identity Trap

Somewhere in the last few decades, Western culture—and Western Christianity along with it—made a profound swap. We traded the language of sin for the language of trauma. We exchanged moral agency for psychological explanation, and we replaced confession with therapy.

This shift didn’t come out of nowhere. For so long and in so many ways, “sin” was weaponised—used to shame, control, and coerce rather than to heal. In many Christian settings, especially, it became a tool for enforcing conformity, punishing difference, and exerting control. The misuse and the damage were real and in plenty of places continue to be so today.

So we threw out sin altogether. The baby with the perverbial bathwater

And in doing so, we have discarded something essential. The recognition that we are not only wounded by the world but are capable ourselves of wounding others. That we are not just shaped by forces beyond us but are also responsible for the choices we make, no matter what has happened to us. That freedom begins not with explanation, but with the truth that a contemplation of our sin reveals.

The Trauma Identity Trap

We have become highly articulate about victimhood. We can name the ways we were hurt—by parents, partners, churches, cultures, and systems. We can catalogue our triggers and trace our pain with impressive precision. All of this has become an open part of even polite conversation when someone asks how we are. And in church circles, it has become de rigueur when asking for prayer.

This awareness does matter.

Naming wounds can be illuminating and necessary. But when trauma becomes our primary identity—when we are defined entirely by what was done to us rather than how we live from it—we enter a subtler and more pernicious kind of captivity.

We can all too easily remain trapped in the past, endlessly narrating our pain, circling our wounds without moving beyond them. And the great irony is this:

A culture obsessed with healing often struggles to become well.

Why? Because we have amputated a crucial truth. We are not only victims; we are also agents. We act. We choose. We participate in the world’s brokenness even as we suffer from it. We wound others even as we are wounded. The biblical word for this agency—and for its effects on ourselves and others—is sin, and where we are sinners.

To acknowledge this is not to blame any victims or minimise trauma. It is to tell a larger truth about the full complexity of being human—and that truth about our sin, paradoxically, is what opens the door to freedom. A freedom that still eludes so many of us.

Christ, the True Victim

Christian theology offers something the therapeutic models of life cannot: Christ himself. In Christ, we encounter the only truly innocent victim. He suffers without deserving it, without contributing to his own destruction through sin. His victimhood is complete.

And what does he do with this?

He does not cling to it. He does not build an identity around it. He does not use it to justify withdrawal, bitterness, or self-protection. He transforms it. His suffering becomes the place where all suffering—deserved and undeserved—can be healed.

The psychological turn and the culture of perpetual victimhood become a distortion of Christ as the true victim because they turn suffering into an identity rather than a passage to healing. In the gospel, Christ is the true victim not simply because he suffers, but because he suffers without being defined by it. He names injustice fully, but he does not organise his life around injury or grievance. He carries suffering through death and beyond it into resurrection. And invites us into the same.

Perpetual victimhood does the opposite. What begins as necessary truth-telling hardens into a fixed self-understanding. Pain is no longer something that happened to me, and becomes who I am. Moral authority is then drawn from my injury rather than my transformation. Forgiveness becomes impossible because it would loosen the identity that suffering has secured for me.

Ignatian spirituality addresses this dilemma head-on with particular clarity. In the Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius invites us to contemplate Christ crucified and ask:

What have I done for Christ? What am I doing for Christ? What ought I to do for Christ?

Notice the movement. It begins not with what was done to us, but with honest attention to what we have done. Not because our wounds don’t matter, but because Christ’s wounds free us from being trapped inside our own.

Why Naming Sin Heals

Various Christian catechisms describe the pernicious nature of sin and its effects on us (e.g., the Westminster Confession of Faith). The Catholic Catechism says it most simply: sin wounds the soul. This wound disrupts our relationship with ourselves, with God, and with others. That isn’t a metaphor. Our choices damage our capacity to love—and to be loved. And here is what our therapeutic age has forgotten:

We cannot heal wounds we refuse to name—especially those we have caused and made worse.

God does not need us to confess because He is uninformed. He needs us to confess because we are. I’ll say that again. God does not need us to confess because He is uninformed. He needs us to confess because we are.

Healing requires exposure. Not only of what others have done to us, but of the ways we have damaged ourselves and others through fear, desire, avoidance, and control.

This is what confession and repentance offer that therapy alone cannot - the restoration of our moral agency. Confession reminds us that we are participants in our story, not merely its casualties. And in that recognition, something remarkable happens. We can become free in the ways we long for and desire.

Sin and Freedom: The Ignatian Insight

For Ignatius, attention to sin is not about guilt or self-loathing. It is about freedom. Sin is understood through the lens of disordered attachment, good things made ultimate things, loves that quietly enslave us.

Success. Approval. Security. Comfort. Control.

None of these is evil in itself. But when they begin to govern our choices, when we sacrifice integrity, relationships, or truth in order to preserve them, they become chains that bind us.

The Ignatian examination of conscience is therefore not an exercise in self-surveillance, nor a catalogue of our wounds. It is a prayerful and honest review of our thoughts, actions, and omissions in the light of God’s love, so that what needs healing, forgiveness, and change can be truthfully named.

It trains our attention to notice where we are bound, where we habitually choose the lesser good, where fear drives our decisions, and where self-protection wounds others. The question is not simply “how was I hurt today?” but “where did I choose unfreedom over love?”

If we have forgotten how to understand sin in this way, we have also largely abandoned the practice of penance, once central to the lives of the saints throughout Christian history. Penance is not about earning forgiveness or punishing the self. It is a concrete response to grace, an enacted turning of the will. Forgiveness heals, but penance rebuilds. It names sin not only as something to be absolved, but as a poison to be detoxed. Penance is the medicine applied to what sin has disordered, an embodied habituated antidote that retrains our desires, heals habits, and restores freedom to us.

In Ignatian terms, this is acting against (agere contra): the deliberate choice of practices that interrupt the patterns which keep us bound. Lust is countered by learning to see others as people to be honoured, not objects to be used. Greed is countered by generosity, especially when holding on to resources feels safer than letting go. Pride is countered by openness to the truth about who we are. Anger is countered by patience, by refusing retaliation, and by choosing the blessing of others rather than harm. Blame is countered by taking responsibility and owning our part, even when explanation or defence comes easily.

None of this is about earning God’s love. It is about cooperating with it. Penance is how grace is given something to work with in real time, re-forming what sin has distorted, loosening disordered attachments, and retraining us toward life. Left unattended, we often continue to cooperate instead with trauma and with our sin, organising our lives around fear, pain, and self-protection. Penance names another kind of cooperation, an active participation with God’s grace that leads not to deeper bondage, but to freedom.

Anamnesis: Remembering Properly

Ignatian practice restores something we have quietly lost the nerve to practise: anamnesis (the act of recalling or remembering past events). Not as rumination or self-exposure, but as remembering that actually changes us. In the Christian tradition, what is remembered is not simply recalled. It is brought into the living presence of Christ so that it no longer governs us. This is what true confession of sin is.

The Daily Examen is not a therapeutic debrief or a moral performance review. It is an act of resistance against the lie that the past must be either endlessly rehearsed, quietly denied, or used as an excuse for our behaviours. We can invite Christ into the concrete details of the day we have just lived. And when we do so:

Nothing is erased, and nothing is excused, so that all may be touched by God.

We remember our sin not to punish ourselves, but to stop protecting us. We face sin not in order to be shamed, but because what remains unnamed continues to rule us. This is not some kind of spiritual masochism. It is Christian realism, in which freedom requires truth, and truth necessitates the courage to confess sin.

Again, none of this denies anything that has happened to us. Christ has entered every place of suffering, including those we did not choose and could not prevent. Trauma is real. Wounds are real.

But here is the unpleasant truth: our cultural moment prefers not to face the fact that the newly speakable truths of trauma can become a new form of captivity.

What began as necessary exposure can harden into identity. Pain, once named in order to be healed, becomes a story we cannot step outside of. The language that freed us from silence now quietly keeps us stuck.

The gospel grants a more demanding freedom. The true victim Christ has not sanctified victimhood as an identity. He has transformed it into a place of encounter. In Christ, suffering is neither denied nor endlessly curated. Instead, it is taken up, borne by, and changed by Him. Participation in His life means that pain is no longer our final authority.

What we need is not a return to shaming religion, nor a spirituality that flatters us by pretending we are only wounded and never responsible. We need a deeper honesty. One that tells the truth about what has been done to us and the truth about what we have done in response. A spirituality of participation, not explanation, and of transformation, not therapeutic management.

Sin wounds the soul. But it also binds it. And only what is faced can be healed.

Whatever happened to sin? We did not abandon it because it was too cruel. We abandoned it because it demanded change. And yet, it remains the narrow door into real freedom.

Jason, this is one of the best pieces on formation I have ever read. Maybe that's because I've never read about the concept of sin in a piece that is so succinct and clear. I love how you've explained it from the ancient Ignatian perspective, as well as from the contemporary lens of trauma. Thank you. I will be referring to this frequently.

At last, a well-argued exposition of a concept I’ve been wrestling with for a long time. Many years ago, I heard Don Williams say to our congregation: “You show me someone who says they are hurt, and I’ll show you someone who is resentful. They need to repent to be free.”

At the time it felt as cruel as it was liberating. I think this is the best articulation I have seen, of the mechanism he referred to in a simple, brutal, catch-phrase.

That, too, was great teaching, and has fed my pastoral practice over the years, but this article is really helpful! Thank you.