Are The Spiritual Exercises the latest Evangelical Christian fad?

Aka can you solve all your problems with an ignatian retreat?

A fad for bored Evangelicals?

Are the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises just the latest fad for bored Evangelical Christians?

There is a surge of interest in the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises amongst Catholics, Protestants of various kinds, and now with Evangelicals.1

When it comes to spiritual formation, Christians are often searching for the next unsustainable high via the new and the novel. We say we want a real profound encounter with God. Still, instead, we are often easily diverted away from any such thing.

Evangelicals sit in a protestant trajectory, catalysed by consumerism, of seeking the latest, greatest move and experience of God. Well-to-do middle-class Evangelical Christians in Victorian times indulged in 'sermon tasting', shuttling between the mega churches of peak 19th-century evangelicalism to compare their favourite preachers. Every Evangelical pastor knows it is easier to gather a crowd around the latest well-known speaker/teacher, platformed with the best music, light show and merchandising, offering personal encounters with God, than for an event about caring for the poor or sharing our faith (aka Evangelism).

So are the Spiritual Exercises just the new kid on the block for Protestant Christians and now Evangelicals? You aren't cool unless you have gone beyond using the Examen and undertaken The Spiritual Exercises.

As with all things discovered or recovered, there is a danger of them becoming 'in vogue' and the latest Christian magic panacea. It is a short hop from a genuine encounter to a trite 'solve all your problems with The Spiritual Exercises’ where the exercises become a kind of Christian magic for some or something others fear they will never attain to understand or get to experience.

An antidote to faddism

But what if The Ignatian Spiritual Exercises are an antidote to much of the faddism of Evangelical spirituality? And what if this was one of the reasons many are discovering and turning to them? What if undertaking the spiritual exercises requires a process and practice antithetical to novelty and faddism?

Once engaged in the exercises, they can inculcate and activate a set of desires and habits that align with the deepest aspirations of Evangelical spirituality.

Those who come to the end of the exercises will face the challenge of sustaining a longer-term engagement with them if they want to. Like everything we seek to incorporate in our faith formation, they can become stale and passé. But even at that juncture, for what comes next after the exercises, they have built into them a philosophy and pedagogy that, if embraced, generates longer-term engagement.

For now and here, I want to focus on the habitability of the exercises for Evangelicals and suggest they might be a route into the faith experience many Evangelicals long for. Indeed Evangelicals, long suspicious or told to be wary of 'anything but the bible', might be delighted to find the exercises are not really about the exercises. They are a means to an end: an encounter with the Lord through prayer and time with his word.

Fears about imagination

Let's deal with now and dispense with the most immediate objection to the exercises by some, which is the role of imaginative prayer. There is a strand and stream of evangelicalism so caught up in propositional and cognitive modes of expression that it labels anything mediative and contemplative as dangerous. This kind of spirituality assumes we think our way rightly through life, like 'brains on sticks’ with worldviews to protect. And that imaginative prayer, like that in the exercises, is a faulty way to pray and opens us up to dangerous beliefs.

But that is not how any human being really lives; we all make meaning using our imagination around what we love, not what we think. None of us thinks our way through life; we imagine our way around our deepest desires, passions and loves. It is one of the reasons some Evangelicals can believe 'correct' things but are living out their imagination for life that seem to betray their 'correct' beliefs with what their hearts are set on. And the exercise wonderfully works with the cognitive and imaginative. In fact, for Evangelicals, the exercises can bring a realignment with the imaginations and beliefs for Christian living. I've written a separate article about imagination and its role in prayer.

What is an Evangelical?

So what is an Evangelical, and who and what about them aligns with the Spiritual Exercises and why?

Being an Evangelical is an example of tacit knowledge, i.e. something you have experienced, that you know you know through experience that is often difficult to put into words or otherwise communicate with others, like being a bike rider. You know how to ride a bike and are a rider, but it is hard to describe and make explicit to someone else how they might ride a bike without showing them.

If we are going to talk about Evangelicals and map them against the exercises, the work of historian David Bebbington will help. He has made explicit what is implicit to those who are Evangelicals, with what is called Bebbington's quadrilateral in his 1989 classic study Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s.

BTW I am not claiming the exercise to be Evangelical per se, but how they are hospitable to Evangelicalism. And in particular, how they might inculcate the best of Evangelicalism and respond to the worst pathologies of Evangelical spirituality.

Succinctly Bebbington's quadrilateral is that Evangelicals, in all their diversity, have four characteristics and priorities in common:

Biblicism: emphasis on the authority and role of Scripture

Crucicentricism: the centrality of the atonement, why Christ died

Conversionism: a focus on how with Christ, humans beings are converted

Activism: that the gospel necessitates action in sharing Christ, social justice, and care for the poor

We can take these four priorities and map them against the nature and practice of the exercises. As I do that, I will also share some of my experiences with the exercises moving from the conceptual to the lived and experienced.

Biblicism

Evangelicals love the bible. They memorise, study, learn, and claim that it is the most essential way to know and encounter God. There is a range of what Evangelicals claim about the bible, with some extremes about literalism as if God downloaded a copy from heaven to us.

But more broadly, to be an Evangelical means to believe the bible is the word of God, inspired by Him and containing his revelation of Himself with His people. To make meaning of life, understand and live in encounters with God requires reading and meditating on his word in Scripture. To be an Evangelical Christian also means to love his word and hide it in our hearts, in the deepest place where the most important things of life live and emerge from.

The exercises have a deeply biblical approach and method. To undertake the exercises requires close and deep contact with Scripture.

The exercises technically involve two modes of prayer practice, meditation and contemplation, where meditation is using our intellect to think about what we believe and why and contemplation is about our feelings and emotions as we encounter God with our senses. But for both modes, it is predominately with Scripture that Ignatius engages us in the exercises. In the exercises, we read Scripture, think about Scripture, and place ourselves with our imagination into Scripture.

For Ignatius;

Scripture has a central place in the Exercises because it is the revelation of who God is, particularly in Jesus Christ, and what God does in our world. In the Exercises, we pray with Scripture; we do not study it.2

To undertake the exercises means to make more of the bible, not less.

And that is my recollection of undertaking the exercises. To get up every morning and read Scripture as the basis for my prayer encounters. To discover the curriculum for the exercises was to read and work through the gospels, alongside other scriptures, and pray through the birth, life, death and resurrection of Jesus.

I have read the bible in a year. Memorised verses. Studied whole books for preaching series. But there was something different in the exercises. Not just a reading of Christ's birth, life, death and resurrection, but a particular kind of guided route through that. The exercises offer no commentary on the bible. They give questions and directions for some and specific maps for reading the scriptures.

In the middle of the exercises, I remember being so excited at reading and praying Scripture that no matter how late I was up, I would still wake early in the morning to read my bible, pray and meet with the Lord. And I discovered how to integrate my imagination with my mind in the exercises.

The exercises are wonderfully person-centred. I found that reading my way into prayer is my go-to. I would read the bible passage assigned to me and a commentary or book related to that passage. Then I would think, journal and reflect. And then, I would reenter that passage with my imagination, placing myself there with Christ. And the Christ I had met in the past and long to meet again, I encountered daily in new and powerful ways.

Indeed when asked about my experiences with the Lord during the exercises, it required me to talk about the bible passage I was reading through which I met the Lord. There is more of the bible in me after the exercises, not less.

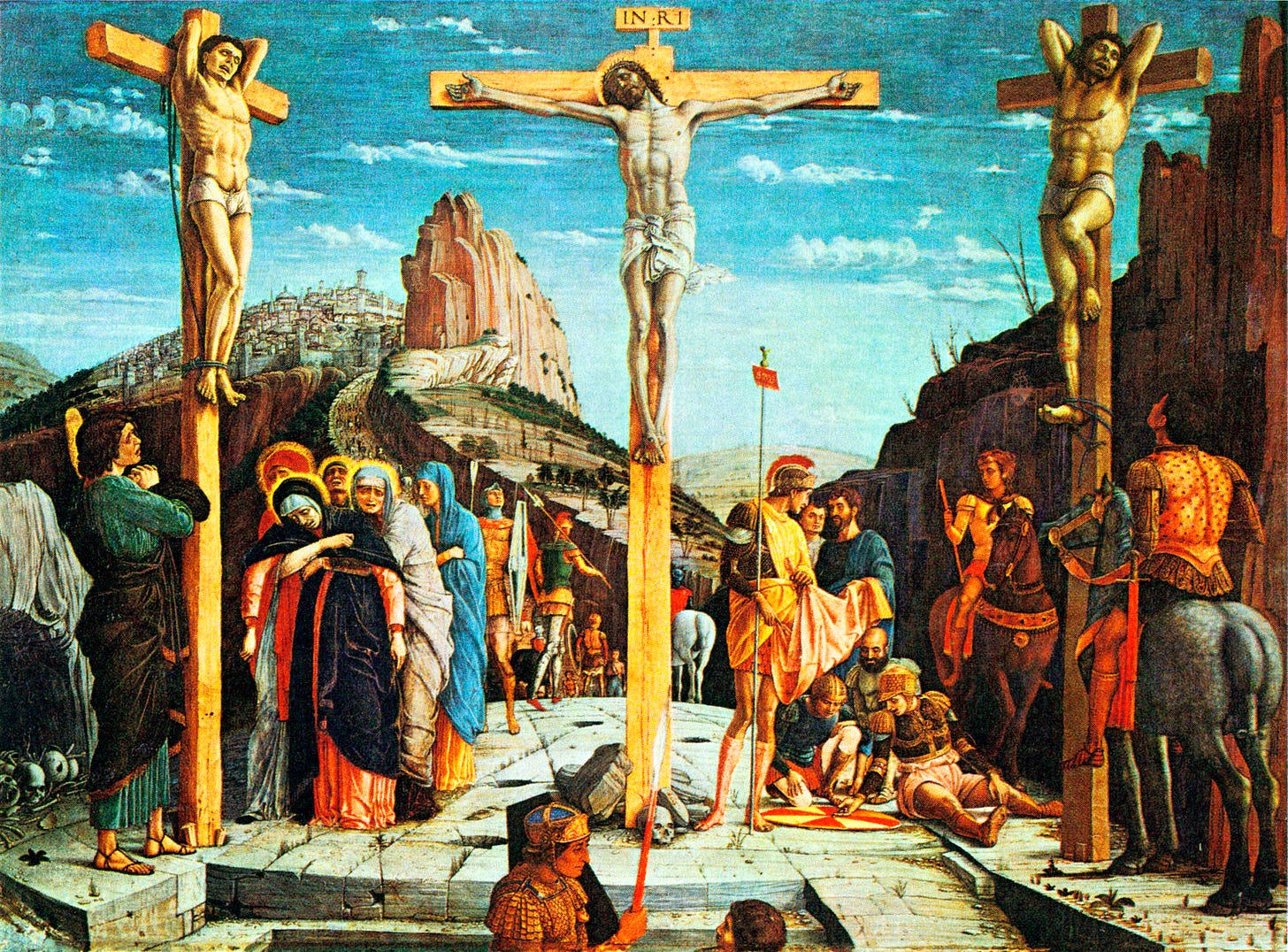

Crucicentricism

For Evangelicals, why Christ died on the cross, what happened on the cross, and how we appropriate the benefits of that, i.e. the doctrine of atonement, is central to Christian belief, experience and practice. There have been many metaphors to describe different doctrinal understandings of atonement in history. A type of Reformed Evangelicalism has claimed penal substitution to be the primary understanding to order and subsume all other understandings of atonement, going as far as to claim the gospel is the one understanding and acceptance of penal substitutionary atonement, i.e. you are not an Evangelical and are not 'saved' unless you believe their version. For other Evangelicals, a more kaleidoscopic, multi-model understanding of atonement prevails.3

In any event, Evangelicals may have different approaches to atonement, but all agree that Christ died on the cross. The reasons for it are vital to becoming and understanding being a Christian. That atonement is literally about at-one-ment, of how God reconciles human beings to Himself through the cross and death of Christ.

There is no doctrinal presentation of the atonement in the exercises. But considering and encountering Jesus on the cross is central to the exercises.

#53 Colloquy

Imagine Christ our Lord present before you upon the cross, and begin to speak with him, asking how it is that though He is the Creator, He has stooped to become man, and to pass from eternal life to death here in time, that thus He might die for our sins.

I shall also reflect upon myself and ask:

"What have I done for Christ?"

"What am I doing for Christ?"

"What ought I to do for Christ?"

As I behold Christ in this plight, nailed to the cross, I shall ponder upon what presents itself to my mind.4

In the exercises, colloquy means to have an intimate conversation with the Lord. Throughout the exercises, we are invited to talk to Christ on the cross, and when we get to the later stages of the exercises, to read, meditate, and focus exclusively on the event and experience of Christ being crucified.

In such prayer, we consider conceptually why Christ died and why so for me and others. But also to experience that with my imagination and explore what it means to experience the cross as we are reconciled to God.

In the exercises, we are invited to stand before the cross of Christ in extended meditation and reflection, to look at the son of God dying on the cross, and have Ignatius say, "Now, what do you make of that?"

While taking the exercises, I came to my time to read passages about Christ on the cross. There is no hiding from the cross in the exercises. I spent two weeks, fourteen days in a row, at the foot of the cross.

From my journal, one moment deep into this experience during what was one of the most painful times of my own life.

He is beautiful. In his destruction is beauty. His soul revealed.

He becomes a tree, the Broom Tree. I see Elijah sitting underneath this tree. He becomes the bronze serpent lifted up, and Moses is standing before him, next to me. He is the tree of life, merging with the tree, his blood causing it to splinter and grow furiously. He is the Vine.

All things are gathered here, all moments of God breaking in overtime with promises, signs and wonders. Also, death, the law, sin, fullness, and Satan gather. The judgement of it all, rendered upon him, is too much to perceive. The weight of it is an antiglory. The oppression is palpable all around us. Like a singularity opening in space and time, sucking all life into its event horizon.

I am now on my own with Him. All are gone. His cross like the trunk of the Broom Tree. Shade over me. I want to die with him. My losses to much for me to bear. I want to sleep and go with him into his death. And this time, I can. This is the place to sleep with him, here at the cross. Not before the cross, but on the cross.

Conversionism

For Evangelicals, being a Christian requires conversion. For our relationship with Christ to transform the mind, the will, identity, heart and being in totality. A profound God-wrought conversion of the type Paul details in Galatians 2:22:

I have been crucified with Christ and I no longer live, but Christ lives in me. The life I now live in the body, I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me.

For Evangelicals, it is not enough to know things about God; instead, to want to be conformed to the image of Christ. And to accept and embrace that we always need more and ongoing transformation.

The word conversion is almost absent from the exercises, but it does not mean Ignatius was not concerned with what we might understand as such. Ignatius was obsessed with movement, noticing if we were moving away from or closer to God. The exercises bring us into contact with God through his word and extended time to map that against our whole lives and notice, i.e. discern if we are moving closer to God or away from him.

The kind of conversation Ignatius was concerned with in the exercises was one where our lives were reformed, re-ordered, and re-aligned around Christ:

#189

Let him desire and seek nothing except the greater praise and glory of God our Lord as the aim of all he does. For every one must keep in mind that in all that concerns the spiritual life his progress will be in proportion to his surrender of self-love and of his own will and interests.5

Ignatius has an explicit and clear agenda in the exercises for us to discern and realise that there is no neutral space in life. We have only two choices: moving towards the enemy, i.e. satan, or towards Christ and discerning the difference so that we might act in response.6 (see #136 and The Two Standards).

The exercises lead us to a reflection and imagination of the consequence of sin and a world formed after the enemy and to imagine one that is formed, i.e. converted to living for Christ. Conversion in the Ignatian senses is affective - soul, mind, spirit, body, and most of all, heart. Conversion is not forced in the exercises. But rather like the hymn When I Survey the Wondrous Cross, in its last verse, having seen, known and experienced the love of God in Christ on the cross, we can make a whole being response under the demands of love:

Were the whole Realm of Nature mine,

That were a Present far too small;

Love so amazing, so divine,

Demands my Soul, my Life, my All.

Any life we make demands much of us, and we can choose what the demands of life are centred around. Once we know and see who Christ is and for us, we are freed into the demands of love for Christ and to offer ourselves to him if that is what we really desire.

During the exercises, I came to the place where I was reading and exploring the calling of the disciples by Christ. I wrote this in my journal, one of my deepest conversion experiences:

I sit with Jesus, the gate in the gate, as a child stroking the veins in the top of his hand. I sit with him as he watches over primary school me about the hear the Lion the Witch and Wardrobe read to me. I lean on him; I ask that my soul be attached to him, hooked by him. I realise again how I have lived from a place of my soul attached to people and things, allowing it to be a portal for anxiety. Yet He is gracious and shows me the times I made decisions for difficult consolation, choosing him when my soul and anxiety attachments would choose something else for false consolation.

And in that, something large in my soul has been stripped back, laid bare, and put to death again and again. This root, the catch in my soul, so big and so deep, generations deep, with soul ties branching out from it. Like a vine from my ancestry, so deep, that gave birth to my parents and their sin and suicides. That root has been exposed; it has taken excavation over time to get to without killing the life from other roots taking root in me. This deeper root, wound around the root of Jesse, that the Lord was seeking to transplant me into...Deep roots have to be exposed, scored, exposed, and treated with glyphosate that kills all life it touches. The better exposed, the more scored the roots, the more precise the treatment to kill the bad root and not destroy other life...

I can see in my moods and interior distress and desolation that wants to attach to that place that used to be in me. To take root, grow, and bring weeds. But it can’t take root now. Hurts and bitterness that allows roots to grow. I used to allow those things to grow within my hurts. Now I hide myself in his wounds, where those roots can no longer grow. He is stripping out those growths and smaller roots. His crucified body, I sit before again, grafted into him. Re-membered to him. Now more than an idea for my brokenness and difficult consolation, but finally life taking shape in me, the stump of my life nearly dead coming to life in him. Deep roots in his deep root. Let there be life.

Activism

It is in activism that Evangelicals are well described and differentiated from others - wanting others to become Christians, wanting their encounters with God to lead to transformation and change in all aspects of society and culture. Knowing who they were in Christ gave evangelicals the confidence to take action in witnessing to others and expressing their faith in daily life.

Activism concerns our response to God and our apprehension at realising his love for us in Christ. Intimacy with God should lead to involvement and activity. Our activity is a diagnostic that shows what we really love. As Clare of Assisi said:

We become what we love, and who we love shapes what we become. If we love things, we become a thing.

The exercises begin with the Principle and Foundation, as the ordering for all our activity in our relationship with God.

The launching point of Ignatian spirituality is that God loves us fiercely, passionately, and unconditionally. Because of this love, God's desires and hopes for us are based on who we are: our gifts, talents, preferences, and joys. What God wants for us is the same as our deepest desires.

What, then, should our response to God be? In Ignatian spirituality, this response is known as the Principle and Foundation7

The exercises have many things at their heart, including friendship with God, spiritual freedom, and discernment. But love is extant at the start, woven throughout, and then made explicit at the end of them.8

As Ignatius notes in the exercises:

i. The first is that love ought to manifest itself in deeds rather than in words.

ii. #231

The second is that love consists in a mutual sharing of goods, for example, the lover gives and shares with the beloved what he possesses, or something of that which he has or is able to give; and vice versa, the beloved shares with the lover. Hence, if one has knowledge, he shares it with the one who does not possess it; and so also if one has honors, or riches. Thus, one always gives to the other.

It is no coincidence that the Jesuits, as ecclesial descendants of Ignatius, are most prodigious and active in history. With the whole world as their church, they got the jump on Wesley, who declared in his journals:

I look upon all the world as my parish; thus far I mean, that, in whatever part of it I am, I judge it meet, right, and my bounden duty to declare unto all that are willing to hear, the glad tidings of salvation.

At the heart of the exercises is an invitation to reflect on how we will live and what we will do in response to the revelation of God's love for us in Christ. Will we say yes to what the Lord Jesus calls us to?

Before I undertook the exercises, I was asked by my spiritual director to reflect and write about where I was with God in part to see if I was ready for the exercises but also as a benchmark to look back on at the end of the exercises.

I wrote this:

Right now, he (Christ) is the lover of my soul. I am captivated by him. I hear him several times a day saying, 'Follow me,' and I keep saying, 'Yes, Lord'. The call to follow, to surrender, is not just intense but sustained throughout the day, every day, for weeks and now several months. I can sit for a couple of hours just to be with Him. To lean against him, to talk with him, for him to talk to me. He is teaching me to pray at the moment, praying for and with me to the Father.

Then about a third of the way into the exercises, I was reading and meditating on Luke 9:57-62, where Jesus calls people to follow him, and they make their excuses one by one. As I placed myself in that gospel story, I wrote this:

He turns to me, 'Jason, will you follow me?' I pause, waiting for my excuse to manifest from within me into words, the thing I must do before following him. Is there anything left within me that holds me back? What is it within me that I lack, that I feel I must attend to instead of letting him attend me? What is my 'first, let me do this, I have to do this'? First, let me make sure Leah (my disabled daughter) is provided for. First, let me make sure everyone in our church is ok? First, let me do what I need to do to feel in control and secure, emails, post, planning, systems, processes, and overwork. There it is. My first in the place of him that makes him second.

I feel my lips move, connected to my soul, ready to express and to justify, my well-rehearsed alibi, that I have repeated to myself over and over and over. But my lips stop and my mouth closes.

I see that swirling thing within me, the root of overwork in my soul from a childhood fear of abadonment. Instead, I want this new thing, what stirs within me differently as I move towards him. Life itself...This is it; this is what he is talking about. To pick up my cross and follow him and have scared fearful part of my die with Him…

...He moves off without announcement and away onto his mission. No explaining, no persuading. This next part is down to us to respond. As I walk away with him, some come with us, some stay where they are, some forlorn walk back.

Jesus is the Vision

At the end of my experience of the exercises, I was more in love with Jesus, more connected to my bible, and carrying a profound sense of healing and transformation. And I was willing to take risks and actions for the Kingdom in a way I had not been free to in a long time. In short, I found all I hold dear and aspired to my Christian faith, and my evangelical spirituality was multiplied through the exercises.

And now, having undertaken the exercises, I am reading articles and books about the exercises. And I find in those writers who have encountered Jesus who are as obsessed and in love with him as I want to be.

I have tried to make the implicit of the exercises and of my evangelicalism explicit. But ultimately, to know the exercises is to do them.

Jesus was and is the vision for Evangelicals, as it was for Ignatius. I leave you with the words of George Aschenbrenner from Stretched For Greater Glory:

The glory shining on the face of the risen Jesus, sparkling like sundazzled snow, is beyond all comparison. The radiance of that sparkle infatuates us in a contemplative absorption beyond our own awareness and reflection. This heart-to-heart encounter with God in the risen Jesus is the core of the Spiritual Exercises. It roots, steadies, balances, and guides the flow of the whole experience. This ongoing encounter stretches our hearts to the limits of the universe and beyond for transformation in a radiance of greater glory meant to nourish and dazzle us all.9

An article by Joyce Huggett, back in 1990, explored why Protestants were turning to the exercises.

O'Brien, Kevin. The Ignatian Adventure: Experiencing the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius in Daily Life (p. 15). Loyola Press.

For a superb summary of views of the atonement, see the article by Steve Burnhope, Beyond the kaleidoscope: towards a Synthesis of Views on the Atonement, and his book, Atonement and the New Perspective.

See #53 of The Spiritual Exercises.

See #136 and The Two Standards.

What the Principle and Foundation Calls Us To, Fred Galo.

I am wondering if moving to your new location sharpened your desire to seek the spiritual disciplines in more of an intentional manner?