#1 Christ's Mental Health and Ours

Part #1 Participation and Humanity

I am constantly humbled by the sometimes hundreds of people who attend seminars I have led on mental health and faith. Rooms full of people, young and old, senior leaders, and those early in their Christian walk. They all have one thing in common—the growing prevalence of mental health issues and caring for family, friends, and colleagues with theirs.

A large part of my life has been about my mental health journey. Key elements generating struggles include chronic childhood abuse, abandonment by my Dad who was bigamously married with a second family, an inherited genetic disposition to mental health disorders, the suicides of both my parents, and crushing legal battles for provision for our autistic, special needs daughter.

My symptoms of poor mental health manifest over time and in the pressures of making a life. Early on, after a breakdown, there was a need for vulnerability in accepting psychological diagnosis, along with taking and trying different medications. Then, there was a need for therapy and the hard work of applying insights from it. Later on, as life became more complex, so did my moments of illness, requiring more psychological inputs and medications.

At their worst, I have found some symptoms utterly overwhelming. Anxiety so intense and pervasive that the dread and panic caused me to dissociate, and feel like I was in someone else’s body. I have had depression, crippling, like a crushing weight pinning me to the bed in despair. Sleep was often the only escape from both depression and anxiety, with the daily waking up a torture of return to the prison of my anguish and distress. And then there have been times of such overwhelm that the idea of ending my life became a coping mechanism.

Yet, in all that, I have managed to move forward, keep working, survive, and find healing and recovery. Psychology continues to inform me, and medications minister to my brain and body. Family, friends, and church have been and continue to be a safe place for healing and recovery.

But there is one dimension: the integration and experience of my faith, which I believe has been the ground of all the elements and moments that have led to recovery and healing. Something from this has come into focus as I prepare for another seminar this summer, and I hope sharing here will help others. I will write a short series of articles, with this post as the introduction to how we might understand how Jesus wants to participate in our mental health and us in His. I hope others might find comfort, relief, and healing from that.

Participating with Christ

One way to understand mental health is holistically, with therapy for the mind and medications for our biology, that we can then bring to prayer. But what if there was something more, something deeper?

One of the greatest pains of mental illness is the sense of being alone. The rest of the world continues blissfully unaware of us, whilst our sufferings are arresting and unrelenting. But we are not alone. Jesus is not just near, but is uniquely able to inhabit and journey with us in our sufferings.

Christians often have little, if any, theology and spirituality of suffering. In a world that seeks to avoid suffering at all costs, Jesus is reduced to someone to pray to to rescue us and help us avoid suffering. This is why some Christians find their faith collapses when real loss strikes. Martin Luther lamented that Christians wanted to bypass Good Friday and go straight to Easter Sunday, eager for the benefits of resurrection but not willing to take the path with Jesus to get there.

Christ calls us to participate, pick up our crosses, and relive and experience his life, death, and resurrection daily—the Christ Event. This Christ Event is the measure for all our lives—the map, the way, and hope for all we are and will be. It is the way to identity, formation, and transformation. It is also the means to healing for our mental health sufferings.

This participation with Christ is far more than cognitive. When we die, it is not our thoughts about Christ that will raise us from the dead. We are part of Him in every dimension and will be raised in Christ from the dead—body, soul, mind, and spirit by the Father. Jesus is careful when he uses metaphors; for example, the Kingdom of God is like this or that. Then, at other times, he is concrete, making claims about what life in him actually is. In Him, we are siblings and heirs (John 14:23). He is the Vine (John 15:5), and we are the branches. He is the Bread (John 6:35) and the Water of Life (John 4:14). There is no ambiguity with Jesus. If we participate with him, it will be for all dimensions of life.

John 6 55 For my flesh is real food and my blood is real drink. 56 Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood remains in me, and I in them. 57 Just as the living Father sent me and I live because of the Father, so the one who feeds on me will live because of me.

So much of the New Testament is about participation in Christ in all dimensions of life. His body and life are given for us; we can give ours in return to him. This is why Paul could write about making up in his own body the sufferings of Christ so that he could participate in the resurrection (Colossians 1:24).

What is not assumed is not healed

This Jesus we are invited to participate with is fully God and fully man. Early in its history, the church articulated that our humanity fell in Adam. As a result, the whole of our humanity requires salvation. And unless Christ took on entirely our humanity, then not all of our humanity could be healed. As Gregory of Nazianzus said, “The Unassumed is the Unhealed”. From Paul to Irenaeus, Athanasius, Augustine, and on up to Luther, Calvin, Bonhoeffer, and Barth, there is an understanding that we “speak of God or Christ becoming what we are so that we could become what he is”.1 More recently Morna Hooker put it this way, that “Christ is identified with the human condition in order that we might be identified with his”.2

This means that our mental health is also something that Christ assumes. If not, we cannot be healed in it. Jesus had a body, a mind, a heart, a spirit and a soul. He experienced all dimensions of mental health - genetics, trauma, stress, and hormones. He had a complete and fully human autonomic nervous system - parasympathetic, sympathetic and enteric. Which means he would experience amygdala hijacks, along with stress hormones cortisol and adrenaline.

Two things come together from above: Our participation in Christ and the full humanity of Christ. To experience the resurrection requires a cruciform life. We participate in Christ’s life and death, and in doing so receive his resurrection power, and also his resurrection body present in ours. It’s why Paul could say:

I have been crucified with Christ and I no longer live, but Christ lives in me. The life I now live in the body, I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me.

Galatians 2:20

Again, not a metaphor but a reality in all dimensions of life, epistemic and ontological. Mind, soul, spirit, heart and body, literally. This means to relive, retell, experience, and continuously embody the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. This is the Incarnation, Passion, and Resurrection. Where is Christ now after his resurrection? He is at the Father's right hand, but also present in those who follow him, bringing our humanity into his likeness and transformation. Our body is part of his body. His mind becomes our mind.

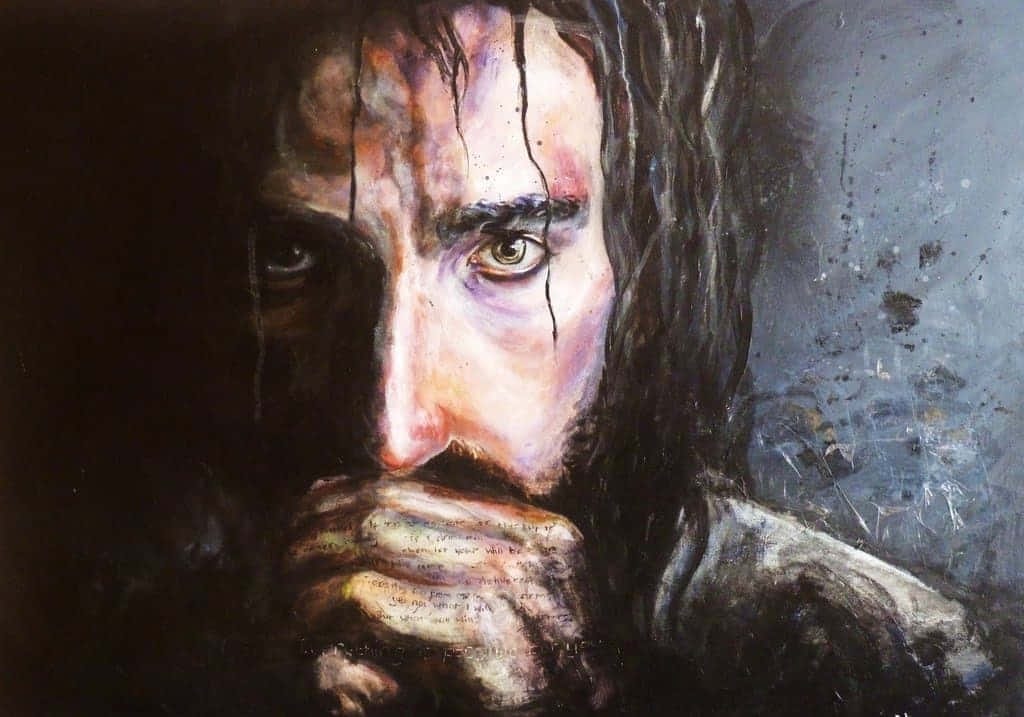

In the second and next part of this short series, I'll suggest that on Good Friday, Christ identifies His mental health with ours and makes a way for us to identify with Him.

From Adam to Christ, Morna Hooker

Thank you for your vulnerability! This was beautiful and comforting to read.