Leadership Scandals: How our deepest desires can protect us from our worst selves

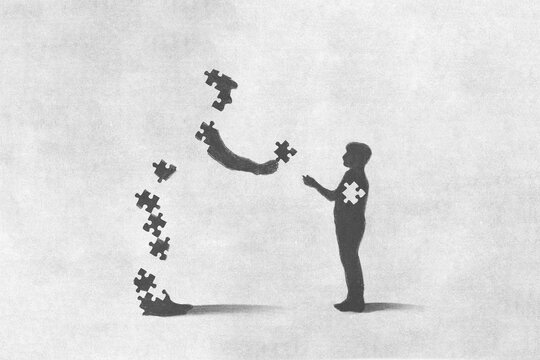

Where we imagine Ignatius taking Thomas Merton through the Spiritual Exercises

Current leadership scandals and headlines have had me mulling over what might be a suitable response. How might leaders be better prepared to avoid and process the things that so often result in their downfall? In particular their desires.

The Thomas Merton Affair: Leadership scandals and a proposal

Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk, one of the most famous and influential Christian writers and thinkers of the 20th century, under vows of Chastity, ended up as a middle-aged man having an affair with a woman half his age. When the affair was exposed, the nature of the relationship became replete with obfuscation and casuistry redolent of current leadership scandals. For a man expert in articulation and expression, there seemed to be a squalidness in the way Merton elided and danced around the truth of the nature of his relationship.1

As I consider the current crisis in leadership and of Christian leaders, I wonder if there is something we might draw on from Ignatius as an antidote to how even our best leaders are sucked into moral quagmires. Something we might run against the story of Merton's affair as a thought exercise about the nature of desire that might help current and future leaders in their own struggles.

Here is my proposal.

Was there a mismatch between Merton's obvious desire for God and his understanding of how God works through our desires to meet him? Are we all prone to a similar mismatch? And, does Ignatius's understanding of desire and how God wants to meet us through our deepest desires contrast, making a better and safer way for us all?

The abnegation of desire

Anyone entering into a deeper prayer experience, seeking to drink from the well of Christian spirituality, mysticism, and contemplation, quickly discovers how all roads lead to Thomas Merton. It is impossible to ignore him or bypass him.

During his historic address to the US Congress on September 24, 2015, Pope Francis lauded Merton, name-dropped and placed Merton alongside Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Dorothy Day as one of the greatest Americans, who "offer us a way of seeing and interpreting reality".

Merton, a Trappist monk, writer, theologian and mystic, produced his autobiography Seven Storey Mountain at the ripe old age of thirty-one. It was an instant bestseller and went on to sell several million copies.

Merton's prose plumbed the depths of the human heart and existence. His writing is disturbing, passionate, evocative, explosive, captivating, compelling, beautiful and, at times, perhaps overly pretentious2 Merton called, and still calls us, into an encounter with God, where all life's desires signpost us to God's desire for us and how we might discover true happiness by God then becoming our greatest desire.

Because I no longer desire to see anything that implies a distance between You and me: and if I stand back and consider myself and You as if something had passed between us, from me to You, I will inevitably see the gap between us and remember the distance between us.

My God, it is that gap and that distance which kill me...I desire...to be lost to all created things, to die to them and to the knowledge of them, for they remind me of my distance from You. They tell me something about You: that You are far from them, even though You are in them. You have made them and Your presence sustains their being, and they hide You from me. And I would live alone, and out of them. O beata solitudo!3

And yet, the God Merton longed to know, and encounter seems perpetually elusive for him. I am not a Merton scholar - there are many - and I suspect more than a few might take me to task for what I am about to claim about him. I have not read Merton's whole corpus. Notwithstanding that, in my readings of him, I find a man desperate to meet God, yet where every encounter seems to lead him into an experience of more distance, not less.4

And I also wonder if Merton was wrong in his understanding of desire. Merton’s route to God was the abnegation of desire, which seemed to generate a dimension to his relationship with God, which would ultimately be revealed through his mid-life affair.

In his vows to God aged thirty-one, Merton describes a speaking by God to him:

I hear You saying to me:

I will give you what you desire. I will lead you into solitude. I will lead you by the way that you cannot possibly understand, because I want it to be the quickest way. Therefore all the things around you will be armed against you, to deny you, to hurt you, to give you pain, and therefore to reduce you to solitude.

Because of their enmity, you will soon be left alone. They will cast you out and forsake you and reject you and you will be alone. Everything that touches you shall burn you, and you will draw your hand away in pain, until you have withdrawn yourself from all things. Then you will be all alone.

Everything that can be desired will sear you, and brand you with a cautery, and you will fly from it in pain, to be alone. Every created joy will only come to you as pain, and you will die to all joy and be left alone. All the good things that other people love and desire and seek will come to you, but only as murderers to cut you off from the world and its occupations[…]5

This is the culmination of Merton's autobiography, in which Merton seems to be the hero with impossible ascetics. Where to meet God is a kind of self-harm and relational and psychological mutilation, enduring a cutting off from people, loves and desires. It is as if the God he desperately wanted to encounter could only be met by being dismembered from the deepest desires of human experience and life. Christ also seems remarkably absent at this intersection of his desire for God, with Merton putting himself impossibly in Christ's place.

On reading Merton’s concluding autobiographical epiphany, a middle-aged me, after over twenty-five years of pastoral ministry, could not help but mutter under his breath, "No wonder this did not end well".

Forget Merton for a moment if I have done him a disservice and just consider church leaders who have mismanaged their deepest desire and shadow selves. Church leaders who run afoul under the pressures of life and leadership due to their deepest desires and unmet needs—distancing, the cognitive dissonance of denial or surrendering to those things.

Desire reveals our false and shadow selves

Merton wrote about the false and shadow self and rightly named them, yet was possibly unable to see how his approach to the false self-created a different kind of shadow.

Every one of us is shadowed by an illusory person: a false self.

This is the man I want myself to be but who cannot exist, because God does not know anything about him. And to be unknown of God is altogether too much privacy. My false and private self is the one who wants to exist outside the reach of God’s will and God’s love—outside of reality and outside of life. And such a self cannot help but be an illusion.

We are not very good at recognizing illusions, least of all the ones we cherish about ourselves—the ones we are born with and which feed the roots of sin. For most of the people in the world, there is no greater subjective reality than this false self of theirs, which cannot exist. A life devoted to the cult of this shadow is what is called a life of sin.6

The logic of Merton's ascetic of self-abnegation leads him to this conclusion about the false self:

...there is no substance under the things with which I am clothed. I am hollow, and my structure of pleasure and ambitions has no foundation. I am objectified in them. But they are all destined by their very contingency to be destroyed. And when they are gone there will be nothing left of me but my own nakedness and emptiness and hollowness, to tell me that I am my own mistake.7

Merton's spiritual ascetic caused him to be unable to see himself before God. Where denial of himself was the only way to be seen by God, known by God, where to have substance came at the cost of being unable to see himself.

Is there anything sadder than these words of Merton?

Every one of us is shadowed by an illusory person: a false self.

This is the man I want myself to be but who cannot exist, because God does not know anything about him. And to be unknown of God is altogether too much privacy.8

Nakedness and midlife revealings

Merton, in mid-life, faced the kind of things mid-life brings to us all - disappointments with vocation, politics and the state of the world, a body that was failing him and required surgery. We can picture the Merton who had avowedly cut himself off into isolation for a way of life where his joy would be pain, and who then faced the pain that comes with all the disappointments of life that accumulate into mid-life. The body does indeed keep the score.

Lonely, unhappy, and vulnerable, suddenly something through a twenty-five-year-old student nurse (Margie Smith) brings into his life what he really craved, hidden under his abnegations of desire—touch, affection, contact, intimacy and love.

In his journals, we get a glimpse of what Margie meant to him:

Yet there is no question I love her deeply, and am drawn to her with an almost agonizing desire sometimes. I keep remembering her body, her nakedness, the day at Wygal’s, and it haunts me. At moments it gets so bad I feel a kind of utter despair at my frustration. I suppose really what my nature, in its hunger, really secretly planned was to have her as a kind of mistress while I continued to live as a hermit. Could anything be more dishonest? I must say I never really accepted the idea, although I really think she would have. I am convinced that if she had come Saturday, it would have been a kind of showdown in which, perhaps, I could have been enslaved to the need for her body after all. It is a good thing I called it off.9

It is as if Merton's false self becomes grounded, earthed and dissipated by the electricity of love and contact with Margie. The nakedness of the woman he loved leading to his own nakedness in all dimensions and aspects of life, is the most honest and revealing of his true self, not the false.

When I read the young Merton of Seven Storey Mountain, I see a man hidden in hubris. When I read about his nakedness and desire, it seems almost Edenic, and he is revealed in his fallenness. It is as if the Father can now say to Merton, 'There you are, I see you now, my beloved; do you now see yourself with me?'

Finding God in all Things: Ignatius and desire

I imagine Ignatius taking Thomas Merton through the Spiritual Exercises as a thought exercise. I wonder if Merton might have with Ignatius found a different way to navigate his desires and to have met the God he so desperately wanted to meet sooner and in a way that might also have avoided the cover-up of his affair.

The simple but profound idea taken from Ignatius is this.

God loves us so much that he wants us to sit with him and follow the deepest desires we have all the way to the end of them to meet God. That God is waiting for us at the end of and underneath our deepest feelings, cravings and needs. The way to God is not the abnegation of our desires but to walk all the way into them to a God that those desires point to.

We can sit with God and talk about our most disordered passions, desire and loves and find not the absence of God but his presence. A God who wants to talk with us and use our honesty about our desires to connect with us and diagnose what we really desire under our desires. Our desires do not separate us from God unless we let them. They can instead be the vulnerable path we walk to find a God who rushes to us like the prodigal father waiting to bring us home.

Ignatius awakened to his love of and encounter with Christ when wounded in battle and convalescing. He had extended times of fevered imagings of the chivalry, great deeds and the women he might romance. It seems there was nothing for him to read whilst convalescing to fuel these fantasies, and instead, to hand were a few books on the life of the saints and Jesus.

So for some reason, Ignatius turned and applied his imagination to those readings, placing himself with Christ and the saints as if he were with them, engaged in their deeds and actions.

And something remarkable happened.

Ignatius noticed that his knightly dreams, whilst initially appealing, quickly faded into emptiness and a sense of lack. But when placing himself with Christ and the saints, he had a feeling of peace, intimacy and contentment that continued with him (BTW, I have written about how I think imagination and encounter with God works, the kind that Ignatius experienced).

On his recovery, as a follow-up to the experience of his imagination of Christ, Ignatius set off on a pilgrimage, intent on walking in the footsteps of the saints and Christ. He got as far as the village of Manresa, in Catalonia, intending to rest, and a few days and stayed there nearly a year. He lived in a cave and took up extreme ascetics, fasting, praying for hours daily, stopping cutting his hair and beard, ceasing bathing and letting his nails grow.

As he tried harder and harder to deny himself, he felt as if God was still displeased with him and even considered suicide. Eventually, at the end of himself, further away from the God he encountered in his battlefield recovery, he stopped to pray by the river Cardener, and the Lord met with him, with an experience of God's love that changed him forever.

Ignatius writing about himself in his autobiography in the third person says:

He sat down for a little while with his face to the river—Cardener—which was running deep. While he was seated there, the eyes of his understanding began to be opened; though he did not see any vision, he understood and knew many things, both spiritual things and matters of faith and learning, and this was with so great an enlightenment that everything seemed new to him. It was as if he were a new man with a new intellect.10

In response to this experience of God's love, Ignatius gave up severe fasting and harsh penitential practices. There was a realisation and revelation of the kind that Robert Marsh describes as being how “Ignatius learned to trust attraction enough to let it be the place where God continued to create him”.11

Ignatius learned that God was to be found not in being cut off from things but through and in all things.

Abandonment: My problem with envy

In making this reflection here, I have paused to consider my desires, those which trouble and unsettle me the most—running what I have suggested here in this article against my own life. As I do that, I have been able to name what I think is the biggest struggle with my shadow self, which has endangered my leadership the most. What I share now is not in any way to compare and contrast myself with Thomas Merton but to show how this Ignatian approach to desire has helped me.

I have suffered from anxiety and depression, and PTSD, all fostered by a childhood of extended abuse and abandonment. My parent’s neglect and harm generated all those sufferings but became a prison of my own making, as all coping mechanisms do.

One day during the 19th Annotation - Ignatian Retreat in Daily Life, I felt the Lord invite me to review an event in my past. The point in time when my Dad announced that he would work abroad and be away for ten to eleven months of the year. It was the moment he realised his emotional absence into something physical, taking himself away until one day he never returned.

I let the Father take me there to that experience and to re-enter it as fully as I could. I noticed the time of day, where we were in our house, and where I was standing. I noticed how ten-year-old me could discern the pretence in my Dad’s explanations for leaving and his false concern for me. I sensed he was excited to leave us, already gone despite standing before me.

I felt the Father ask me - How did you feel at that moment? Like I wasn't enough for him, I replied. I saw how a chasm of lack had opened up in me at that juncture. I was not enough, and I would not have enough. And life then bore that belief out, evidenced by how we were nearly made homeless when I was a teenager.

Something took root and grew in that chasm - a way of coping and a necessary survival mechanism but also something else - envy.

When I say envy, I invoke how early Christian monks understood envy (invidia) as one of several key excessive versions of one's natural faculties or passions.12 I understand envy as a deep-seated sense of lack and shame.

Thomas Aquinas diagnosed envy as "self-inflicted pain wounds the pining spirit, which is racked by the prosperity of another".13 My proclivity to envy was not resenting others prospering, but instead, was something turned inwards where I saw myself as having less as being less.

My inner narrative was that my life might have been much better if I had what other people had, the support and resources I saw them with. And there was truth to that, but also something damaging to me. Envy was what led to me becoming a workaholic, unable to trust that God would provide for me. Envy led to planning, overplanning, and wanting to control things to be safe.

So as the Lord walked me into that memory, I came face to face with my lack and envy. Then the Father spoke something else to me.

You have always been enough. You were the son of a prodigal son, abandoned in far off land. I sent my son to rescue you and bring you home. After all these years since my son met you, it is time to come home to my house, the Father's house.

And something broke in me.

Scripture flowed from my heart and soul into a verbal confession - the Lord is my Shepherd; I lack nothing. I was enough and lacked nothing. Under the prayer directions of Ignatius, I had walked all the way into my deepest desires and found the Father waiting there for me. My greatest desire to be enough and have enough was the source of an encounter with the God the Father.

Walking all the way into our deepest desires

So I end where I began.

What if the downfall of some Christian leaders, through things which we are all prone to, might be due to a mismatch between our desire for God and our understanding of the way He works through our desires?

What might happen if we walked all the way into our desires and met God there?

Merton was far more explicit with details in his journals, See Shallow Calls to Shallow, Gary Wills, and Beneath the Mask of Holiness: Thomas Merton and the Forbidden Love Affair That Set Him Free, Mark Shaw.

For a critique of Merton's prose and see Thomas Merton and the Language of Spirituality, Thomas Larson.

Thomas Merton, Seven Storey Mountain: Fiftieth-Anniversary Edition, 672.

Thomas Larson, the literary critic, wonders the same about Merton; for example, "I’m reminded of a sentence from his The Living Bread (1956): “As long as we are in this world, our life in Christ remains hidden.” What kind of a Christian are you if your life in Christ “remains hidden”? ...The spiritual life, according to Merton, is one of random tremors, of unpredictabilities. The individual’s constant supplication for grace suggests that grace is common. Not at all. What makes Merton interesting is that he is not saved by such insights...Heaven and its spiritualizing presence is almost entirely unavailable. And, as Merton surmised early on, seeking it outright means you can’t have it. I think the elemental question about Merton the author is, how might writing help him find that hidden “life in Christ,” even when he says it’s absent?"

Seven Storye Mountain, 672.

Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation (New Directions Paperbook: 1972), 34.

Ibid., 35.

Ibid., 34.

Thomas Merton, Learning to Love, 194.

Ignatius, Autobiography, #57.

Rob Marsh, Imagination, Discernment and Spiritual Direction, 14.

See the Capital Vices, aka seven cardinal sins.

Thanks Jason for this. This section, anchored by this thought is very much needed: “ The way to God is not the abnegation of our desires but to walk all the way into them to a God that those desires point to.”

‘There you are, I see you now, my beloved; do you now see yourself with me?'

Yes! In that bleak place of raw revelation, the Lord comes near in merciful love. Thank you for again reminding me of this gift today.