Love, Desire, and Identity

The not-so-secret path to becoming who you want to be and bridging the gap between what you believe and what you do

It's all about Identity

You may have heard of James Clear's book Atomic Habits. It's a best seller and has influenced many people by helping them understand and change their habits to effect change.

Clear has meticulously researched and distilled the key findings of experts, including behavioural scientists, neuroscientists, and physiological psychologists. His book is a treasure trove of knowledge about how humans form and change habits.

His most important discovery is at the beginning of his book: What we do shapes who we are, and who we are shapes what we do. Underlying this is the principle and sole driver of all we do: identity, i.e. who we are. Our identity determines our habits, and our habits shape our identity in a mutual, reciprocal relationship.

"True behavior change is identity change." 1

Our existing habits flow from our identity, and changing them requires a change in identity. As Clear says, the goal is not to read a book but to become a reader, not to learn an instrument but to become a musician

Clear gives an example of a smoker and a non-smoker. Offer a non-smoker a cigarette, and they will readily decline. An ex-smoker will struggle to refuse a cigarette until their identity becomes one of non-smoker.

This identity and habits dynamic is part of life and Christian identity formation. Are we people of prayer, or are we always deciding in the moment whether we might pray? Are we worshippers, or are we someone who decides week by week whether we are going to worship? Think about the changes we want in our faith life. Are you constantly deciding whether to do something or have you resolved something about your identity that automatically leads to changes in what you do?

If we want to change, all the evidence and science point to two things that have to happen:

1) Decide the type of person you want to be

2) Prove it to yourself with small wins2

In other words, who do you want to be? What do you want and desire at the deepest level of who you are? Figure that out and then start to take identity-based steps and actions out of that desire. That will then begin to form your identity, and your changing identity will generate changes in your behaviour that create more of the identity you desire.

What we love, and desire is what we do

In the 4th century, St Augustine got the jump on James Clear and science and diagnosed our identity and habit dilemma. Augustine articulated something from scripture, pastoral observation, and theology that science and sociology now confirm.

What we love (desire) is what we do, and what we do shapes what we love.3 When Augustine talked about love, he also meant the affective dimensions of desire and wanting. If there is a gap between what we say, believe, and do, it is because of something that we want, desire, and love within us that directs our habits. We are desiring beings. We are all oriented to what we want, crave, desire, and love.

You are what you love because you live toward what you want4

The only question is, what do we desire and want?

The writers of the Bible were keen observers of human nature and behaviour and, inspired by the Spirit, repeatedly pointed out how love and desire are at the root of human identity and behaviour. Paul prays that the Philippian church will grow in Love (Phil 1:9). Jesus, recapitulating Deuteronomy, tells us to love God with all our hearts, souls, strength, and minds (Luke 10:27), i.e., with all we are, are the deepest levels of who we are.

Re-calibrating our hearts

God created us out of His love, loving us into being. Christ was wholly ordered around that love, returning Himself to God and inviting us into the same—to learn to love God so that God becomes our principal desire, aligning us and ordering us around who we were created to be.

Here we have a catch-22. We will not change what we love and desire unless we change what we do. We are already perfectly aligned with what we do for what we want. Yet, the desire to change is enough for God to work within us.

Thomas Merton offers us a now well-known prayer related to this dilemma:

But I believe that the desire to please you

does in fact please you.

And I hope I have that desire in all that I am doing.

I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire.

To want to change, to turn towards God more, just that desire to desire change, is a sign of God at work wooing us in His desire for us. God always makes the first move towards us and the next. Changing our identity means assessing our desires and wants and then re-calibrating those with new habits around new and different loves. How do we do that?

We engage in worship practices.

To paraphrase Augustine, the purpose of worship is to train us to love and desire rightly.5 Worship offers affective experiences that focus our attention, helping us notice and discern what we love and compare that with our encounters with and relationship to God.

This is why so many people have met God in a worship encounter. Entering a space and place where others are worshipping God can be an opportunity to see the desire and love of others for God and kindle that in our hearts. Most people capture a love for something in life, a sport, hobby, or activity, by seeing others doing something they love and participating in it with them. Love and desire are infectious.

I met Jesus in a worship service.

I went into a church worship service for the first time when I was turning seventeen. I was only there to protect my mum from what I assumed would be crazy Christians. And I was utterly abducted by the experience.

They were not crazy but kind, caring, and welcoming. And they sang songs full of words about love, desire and passion for God, some with arms raised, some with tears on their cheeks. I realised the words they sang they believed, but more than that, this was something most profound for them about life itself. I was captivated. It took my mixed bag of conceptions about God and sifted them into something personal and immediate to consider. I returned to the evening service and met Christ in person that night.

The Spiritual Exercises: A course in desire, love and identity

One way to understand the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises is as an intense and extended worship experience. In their nature, they are about giving time, attention, imagination, and our senses to review our deepest desires and loves with God.

The Exercises work at a profoundly affective level, co-inhering with the nature of science and behavioural dimensions of identity change. However, as worship, they are something much more and involve encounters with the living God. The Exercises as acts of worship do not just compete with secular, consumer and all other imaginations. They are connected to the one who made us with all our desires and wants (I wrote about how we can trust imaginal times in prayer with God here).

From start to finish, the Exercises direct us to be honest with God about what we desire and love and then connect that with reading and praying about Jesus's life, death, and resurrection. Ignatius was confident that those taking the Exercises would meet Jesus and have the opportunity to fall in love with Him, much like he had and those in scripture who invited their friends and family to come and see this Christ who had captured their hearts.

But while one is engaged in the Spiritual Exercises, it is more suitable and much better that the Creator and Lord in person communicate Himself to the devout soul in quest of the divine will, that He inflame it with His love and praise, and dispose it for the way in which it could better serve God in the future.6

Love is spontaneous and practised

I fell in love with my wife when I was eighteen. Over the years, we have often asked why we love each other. We can name things and attributes about each other that we love. But ultimately, our love comes down to something fundamental and non-contingent. We just do love each other. At the bottom of the reasons for love, there is no reason, only love itself. When asked why I love Christ, I can give you many reasons, but ultimately, I just do love him. He loved me into being, and I return myself to him in love.

And yes, over the thirty-seven years my wife and I have been together, first dating, then engaged, and then married, we have had to work on our love as it has ebbed and flowed. I have had to work and will continue to work on my love for God.

During my experience of the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises, in my prayer imaginings, there was a moment when I felt the Lord show me something. I was taken back to a memory when I was about five years old and had recently started school. It was my favourite time of the school day when our teacher would invite us to sit on a rug, and she would sit in front of us on a chair to read a book to us. One of those books was The Borrowers. But today was to be the start of listening to a new book.

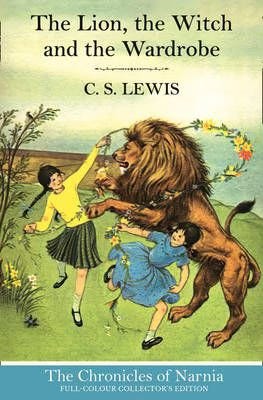

The sun shone through a window, creating magical dust motes dancing in the air. We were shushed into expectant silence. As the new book was raised and opened to be read, the cover hoved into view. Two young girls danced with and placed a flower garland around a lion in a cliff-top garden by the sea. It was The Lion the Witch and The Wardrobe, with the Pauline Baynes illustration. As my teacher read, I heard about and fell in love with Aslan.

In my unfolding prayer imagining, I saw Jesus sitting behind five-year-old me, watching me in delight as he saw me captivated by this story about him—a story that would fuel my imagination, capture my heart, and prepare me to understand who he was later in life. He was smiling, anticipating the day I would walk into my first worship service and meet him.

I retold this story to my spiritual director, who listened carefully and then asked why Jesus might have been delighted and smiling at the younger me. "Because he knew I would love Him," I answered.

Some thirty-nine years after meeting Aslan in person in that worship service, His love for me has never failed. But mine for Him often has, due to the vicissitudes of life and my lack of fidelity within those. Yet something took root in my core, which has grown over the years from someone who had met Jesus to someone who followed Jesus to someone whose life is Jesus.

I have been crucified with Christ and I no longer live, but Christ lives in me. The life I now live in the body, I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me. Galatians 2:20 NIV

My wife and I know that for as long as we are alive, we have much more to grow into in our relationship and out of love for each other. And how much more so in my relationship with Jesus. He and I have so much more to discover and become. My identity in Christ is, in many ways, settled, but it is by no means at its peak and culmination.

I close with this prayer that describes so much of all this article has been about.

Fall In Love

Nothing is more practical than finding God, than falling in Love in a quite absolute, final way. What you are in love with, what seizes your imagination, will affect everything. It will decide what will get you out of bed in the morning, what you do with your evenings, how you spend your weekends, what you read, whom you know, what breaks your heart, and what amazes you with joy and gratitude. Fall in Love, stay in love, and it will decide everything.7

James Clear, Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones, p34.

James Clear, Atomic Habits, p39.

For the most outstanding presentation of Augustine's idea, see James K. A. Smith's You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit. It is comprehensive, readable, and compelling.

James K. A. Smith, You Are What You Love, p13.

To explore this notion more, see Charles Mathewes "On Using The World," in Having: Property and Possession in Religious and Social Life, eds. William Schweiker and Charles Mathewes.

Louis J. Puhl, St. Ignatius of Loyola, The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius: Based on Studies in the Language of the Autograph, paragraph #316.

From Finding God in All Things: A Marquette Prayer Book, Marquette University. Often attributed to Fr. Pedro Arrupe, SJ (1907–1991), but by Joseph Whelan, SJ

Hi Jason, I really appreciate your comments on Ignatian Spirituality. I have spent the last ten years living and breathing the Ignatian Exercises through an experience of the Exercises that I developed called Transformation Intensive. I think you are right on concerning the Exercises as an experience of sustained worship!

As I began reading this I was waiting for this line;

“In the 4th century, St Augustine got the jump on James Clear” 😅