The Unbranded Life

How to escape the destructive power of the 'psychological turn'

Summary: Jason diagnoses the spiritual and psychological malaise of our age, where identity is reduced to fame, brand, and self-curation. He explores the cultural “Psychological Turn,” tracing how beliefs have shifted from being anchors in shared public life to private, curated selections. He shows how such identity now feels hollow, anxious, and fragmented—“ontologically homeless.”

Drawing on Christian traditions, especially Ignatian spirituality, he offers a counter-narrative: true identity is received, not constructed, and freedom is found not in limitless autonomy but in attachment to God. Through practices like the Examen and imaginative prayer, we can recapitulate our stories into Christ’s redemptive narrative. The conclusion is urgent: the gospel doesn’t ask us to find ourselves, but to lose ourselves and be found in Christ.

…there has been a shift “from a world in which beliefs held believers to one in which believers hold beliefs.”1

We live at a time when we believe we should have no story, except the story we chose when we had no story - Stanley Hauerwas

For much of Christian history, belief was not a private preference but a public truth accepted in all dimensions of life. People lived within a created and ordered world—God’s world—where truth, goodness, and identity were received, not constructed. And most definitely not self-made.

Faith was something that held you.

The self was not a personal project, but a gift that required reception from outside of the self. Belief wasn’t something we chose—it was something that chose us.

But today, something profound has shifted.

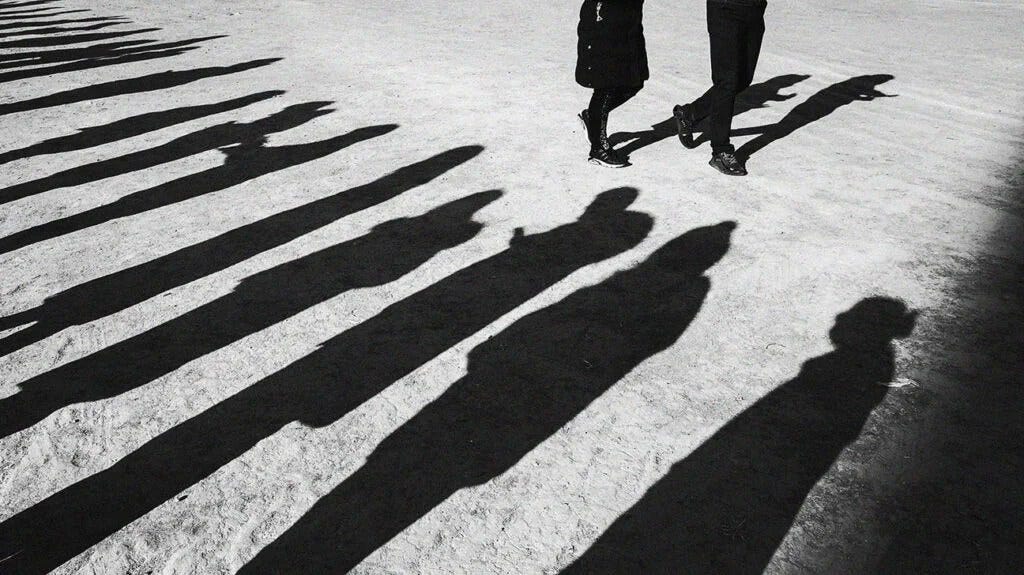

We live in the age of the cult of the self-made self, where beliefs are curated, identities are performed, and meaning is something we construct rather than receive. We are overwhelmed with a vapid parody of the real drama of human becoming. And its effects, unsurprisingly, are both spiritually vacuous and psychologically ruinous.

Pick and Mix: How Did We Get Here?

The modern West has undergone a Psychological Turn, where inner experience is seen as the highest authority. Human meaning, identity, and morality are now largely understood through psychology—a field only emerging in the late 19th century—rather than theology, philosophy, or tradition. Instead of beginning with God, nature, or inherited wisdom, we begin with the self. Who I am is who I feel myself to be; truth must align with authenticity, and identity must reflect personal desire.

Several cultural forces have shaped this moment. Rationalism, secularism, and consumerism have pushed the sacred to the margins, hollowing out the self. Into this vacuum, psychology has entered—sometimes as a healing force, sometimes as a replacement—offering meaning in a world where transcendence is now quiet.

But in collapsing identity into mere affect, we risk creating a kind of emotional cul-de-sac: a self so turned inward that it can no longer hear the call of anything or anyone beyond it—not even the voice of God.

As Vincent Miller observes, belief itself has become commodified. Spirituality is now bricolage—a consumerist mix of quotes, mindfulness, affirmations, and rituals, chosen for comfort or appeal.

We no longer inhabit a tradition; we shop for one.

Faith becomes a collection of fragments, assembled to support the self we wish to create. Beliefs are picked, mixed, and discarded as needed to sustain our self-made identities.

This is not about the maturing of faith, which lets go of simplistic external beliefs to integrate more mature notions from within. Instead, it is a pastiche, mood-driven disorder. This amounts to nothing more than an ontological homelessness. Severed from any transcendent source, the self becomes not luminous but weightless—without inheritance, without anchor, without purpose.

This is the cultural air we breathe. But it comes at a considerable cost.

For in truth, no one is self-made, in the deepest, metaphysical sense. We are, whether we like it or not, contingent creatures—dependent, received, and radically given.

The Destructive Power of the Psychological Turn

We are now told—often with striking conviction—that identity lies in the swirling shallows of inner sensation. Truth has become a matter of subjective resonance; authenticity is the new cardinal virtue, and constraint, the unforgivable sin.

Where freedom once meant the capacity to live well within limits—shaped by virtue, truth, or divine order—it is now framed as liberation from any external claim. Tradition, authority, biology, religion, even community—these are increasingly seen not as sources of wisdom or belonging, but as oppressive forces to be cast off. The only valid authority left is the self.

Anything that provokes inner discomfort—particularly if it challenges our sense of identity or desire—is treated as an affliction to be cured. Traditional virtues like humility, obedience, or chastity are recast as repressions. In their place, self-expression, self-assertion, and self-construction are crowned as moral goods. To yield to anything beyond oneself is considered inauthentic, even weak.

Belief in God, once a matter of truth and trust, is too often reduced to a therapeutic tool—something to help me feel better, be more fulfilled, or escape discomfort. God becomes a mirror for the self, rather than a source from beyond it.

This modern autonomy is celebrated, yet it comes at a cost. If I alone must invent, express, and sustain my identity—if I must continually justify my own worth—I live under constant pressure to perform.

And we see the fruit of this. Rising anxiety. Widespread burnout. A quiet, persistent despair beneath many lives, both public and private. The myth of the self-made person exacts a heavy toll. For without a deeper source of meaning or belonging, the self becomes both bricoleur, as Vincent Miller suggests, and prisoner, locked within the fragile architecture of its own making.

What appears liberating is deeply destructive—spiritually, psychologically, and relationally:

It isolates. We become authors of our own meaning, no longer participants in a shared story—God’s story—with others. Identity is self-scripted, not received in relationship.

It destabilises. Identity becomes a fragile performance: carefully curated, easily threatened, and always in need of affirmation.

It fragments truth. When every personal story is sovereign, truth becomes a contest. We are left vying for attention, competing for narrative dominance.

It burdens the soul. The demand to invent, project, and sustain a coherent identity weighs heavily. The result is often anxiety, shame, and quiet exhaustion.

Christianity tells a different story—one of grace, not self-construction but co-construction with a God who made us and loves us.

Follow The Desires of Your Heart

It does little good to rail against the freedom the modern self demands. That is like shouting into the wind. We might make some headway by highlighting the harmful effects of this vision of freedom, but we are quickly pulled back into our narcissism and addiction to self-creation.

Instead, we might heed St. Ignatius and follow our deepest desires—even those that appear disordered at first. Ignatius believed that our most authentic desires are planted in us by God. Beneath superficial wants and distorted cravings lie holy longings: for love, meaning, service, and union with God. These are not distractions from the spiritual life—they are the spiritual life. To follow them is to cooperate with grace.

This means walking fully into our desires for freedom and asking what we are truly seeking. Ignatius teaches us to pay attention to our desires because, when rightly discerned, they lead us toward the life God desires for us. But to follow these true desires, we must be free—free from disordered attachments, compulsions, and the exhausting pressure to curate a self. Without this interior freedom, we chase what we think we want, yet remain restless, fragmented, and burdened.

In other words, if we dare to explore our desires for freedom, we may find God asking: Are you truly free in your pursuit of freedom? And in that question, we might encounter not only God himself but also his invitation into the freedom he longs to give us—as his beloved creation. There is a profound, identity-shaping discovery to be made in that encounter. It is to receive and carry within us a dignity that is not earned, and a calling that is not self-appointed, but lovingly given, where:

• We are created, not self-assembled.

• We are relational, not solipsistic.

• We are iconic, not consumable.

This is not psychology. It is metaphysics baptised in the Holy Spirit’s fire.

In other words, we are not just talking about feelings, therapy, or self-help. We are talking about the very nature of human existence—who we are before God—and this truth is not a cold, stultifying abstraction but alive, burning, and personal through the presence of the Holy Spirit. It's not therapeutic; it’s cosmic reality on fire.

In this reality, we are not free to become whoever we choose, but in Christ, we are free to become who we were truly meant to be. And no human being has yet exhausted the limitless depths of their identity in Christ.

Participation not Performance

Here, Ignatian spirituality offers quiet wisdom. In a world of noise, speed, and striving, it invites us to listen—to notice where God is already at work in our desires and disappointments.

We are not called to construct improved versions of ourselves. We are invited to become who we already are in the eyes of God.

As Irenaeus taught, in Christ humanity is recapitulated—gathered up, healed, and made whole. Our fractured identities are not erased, but gently rewritten by love. This is no small claim. Modern attachment theory only confirms what the mystics have long known: identity, peace, and wholeness arise not from autonomy, but from secure love.

Ignatian practice—through the Examen, imaginative prayer, and spiritual direction—nurtures this attachment to God by helping us revisit and reinhabit our lives in prayer. We do not recall our stories alone, but with God. In this sacred re-telling, our memories, wounds, and longings are drawn into Christ’s own story—redeemed, reframed, and made whole.

As Christ gathers all of humanity into himself, so too in prayer we begin to see our lives folded into his redemptive pattern. The soul is trained not to invent itself, but to receive itself—moment by moment—from the gaze of divine love.

One way to understand the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises is as a school of freedom. That and wider Ignatian spirituality, with its deeply incarnational grammar of prayer and discernment, offers a quiet rebellion against the cult of the self-made self. Its concern is not self-optimisation, but inner indifference—a freedom from disordered attachment, so that one might be fully available to the love and will of God.

In Christ, the human story is not erased but retold. He gathers our fragments into himself, as the incarnate Logos—not to offer a new brand, but a new nature.

We are not summoned to “find ourselves.” We are called to lose ourselves and be found in him. For the gospel does not call us to become better versions of ourselves—it calls us to become new.

Epilogue: The Collapse of the Self-Made Soul

The self-made self is a fiction with a high body count. It exhausts the psyche, erodes the soul, and disintegrates community. Its gospel is anxiety. Its sacrament is branding. Its eschaton is burnout.

But Christ offers a better way: not freedom from truth, but freedom in truth. Not a curated identity, but a crucified and resurrected self. This is the quiet miracle of the gospel: that in losing ourselves, we find ourselves. That in laying down the burden of self-construction, we are free to live out who we were meant to be.

In Christ, you are not curating a self. You are receiving a life. Not freedom from all constraints, but freedom for the glory of becoming fully and joyfully human in Him.

We are not our own. And thanks be to God for that.

Bibliography

For further reading relating to issues, concepts, and topics above, see

Theological & Philosophical Foundations

Irenaeus of Lyons, Against Heresies – The foundational source for recapitulation.

David Bentley Hart, The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, Bliss – A deep dive into metaphysics, divine gift, and critique of modernity.

James K. A. Smith, You Are What You Love – Explores liturgical anthropology and how desire shapes our being.

Vincent J. Miller, Consuming Religion: Christian Faith and Practice in a Consumer Culture – Dissects the commodification and bricolage of belief.

Charles Taylor, A Secular Age – The definitive cultural history of the modern self.

Carl R. Trueman, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self – Engaging commentary on expressive individualism and identity politics.

Ignatian Spirituality & Practice

Aschenbrenner, George A. Stretched for Greater Glory: What to Expect from the Spiritual Exercises - accessible guide opens the heart of Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises and shows how the exercises are not a psychological fix, but a spiritual formation

St. Ignatius of Loyola, Spiritual Exercises – The cornerstone text for Ignatian formation.

David L. Fleming, Draw Me Into Your Friendship: The Spiritual Exercises—A Literal Translation & Contemporary Reading – A faithful modern rendition of the Exercises.

Margaret Silf, Inner Compass: An Invitation to Ignatian Spirituality – An accessible guide to Ignatian discernment and freedom.

Psychology & the Modern Self

Philip Rieff, The Triumph of the Therapeutic – A seminal critique of therapeutic culture.

Dan P. McAdams, The Stories We Live By – A deep exploration of narrative identity from a psychological perspective.

Vincent Miller, Consuming Religion, p. 90.

Fascinating read, Jason. As an American, it’s difficult to not see much of the American Church in the camp of the self-made self, as the descriptors align closely. I wonder what role the church has played in contributing to the demise of Christian community, identity, and belonging? I think lack of history is one area where American churches fail to understand and communicate many of the points mentioned. Many pastors and fellow Christians know nothing of Ignatian spirituality. Even more have been taught that desires are sinful and our heart’s are filled with deceit- neither are to be trusted. It’s a theological conundrum that takes years to untangle, usually, as you noted with a set of open-handed practices and a spiritual guide/companion/director. While I appreciate your assessment, I fear many churches and congregants (professing Christians) in America see nothing wrong with their hollowed out, self-made theologies and ways of being. Thoughts?