The War for Your Imagination

Reclaiming reality when screens steal your soul

Simulation and the Shrinking Imagination

Ten minutes, maybe twenty—perhaps an hour. A reel of someone’s flawless kitchen, enviable holiday, sculpted body, picture-perfect relationship. Then a film trailer, bursting with visual spectacle and sonic overload, left you hypnotised. And just like that, you slipped into the current: an endless stream of soundbites, images, and videos, each one auto-playing, demanding nothing from you, not even a click.

You watched, swiped and scrolled as each headline or post delivers micro-hits of dopamine and cortisol, activating your amygdala and heightening vigilance, keeping you scrolling as your brain hunts for more perceived threats, while your prefrontal cortex, responsible for reasoning and emotional regulation, is quietly hijacked by the loop.

You stop scrolling, and there is — almost imperceptibly — a rupture in the seamless stream of images, headlines, and curated moments. It may be something physical — the stiffening of your back, the ache behind your eyes — or that small, quiet realisation of a thinning out of your being:

Why am I still here?

In that instant, a certain lucidity intrudes. The mind, a moment ago compliant to the dictates of the feed and its restless summons, begins to reawaken. The higher faculties stir; the appetite for one more flicker of novelty loosens its hold.

Then, almost without effort, your attention turns inward — to the weather of the soul. The climate is heavy: a mixture of restlessness, irritability, and fatigue. Your body keeps score, gives its testimony with candour — the knot in your chest, the weight in your jaw, the shallowness of your breath. To name these — I am anxious, I feel diminished, and sometimes, sordid and sullied — is already to lessen their hold. Light seeps in, and the interior noise begins to quieten.

And here you stand at a small but decisive crossroads. One path draws you back into the churn, into the mechanical liturgy of ceaseless content, each morsel promising more than it could ever bestow. The other invites you into something altogether different — the stillness of prayer, the patient company of Christ, the kind of attentiveness that welcomes reality as it is, not as it is packaged.

Such moments are thresholds: to turn aside from the scroll is to step, however falteringly, towards the Presence who is always near, yet waits to be noticed.

We live surrounded by spectacle and simulation. Movies so sharp they pull you into another world. Games that lay out vast landscapes, promising you can go anywhere. VR headsets that trick your senses into thinking you’ve stepped right into the scene. Social media feeds roll on without end, offering the polished highlights of other people’s lives. It all promises to make us feel more connected, more immersed.

But here’s the thing — the more these tools try to give us reality, the more they take us out of it.

A film hands you the exact face the director wants you to see, the colour scheme they chose, the soundscape they built. A game talks about freedom, but every choice has already been decided by someone else’s code. Social media lets you “follow” people’s lives — but only the edited, filtered parts they want to show you. We’re given endless images of life without ever having to live it. And the more we feed on those images, the smaller our own imagination becomes, and the harder it gets to be present, to live into the reality God has for us to experience.

Ignatius and the Sanctified Imagination

Ignatius of Loyola first stumbled onto the deep spiritual power of imagination in a moment he didn’t plan for. Wounded in battle and stuck in bed, he found his mind wandering. At first, it was to the things he knew — dreams of glory, fame, romance. His version of doom-scrolling entertained him for a while, but left him hollow. Then he began to imagine something different: a life lived for God, marked by love, courage, and service. Those daydreams didn’t fade into emptiness; they left him with a deep, lasting consolation. And that’s when it hit him — God could speak to him through his imagination.

Out of that realisation came one of the most powerful tools of prayer the Church has ever known: Ignatian contemplation. In his Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius invites us to step right into the Gospel scenes with all five senses. See the dust rising from the road, hear the voices in the crowd, feel the rough weave of a cloak, smell the bread fresh from the oven, taste the salt of the sea air. When we let the story come alive like this, it moves from being words on a page to an encounter that stirs our heart, shapes our desires, and begins to change us.

Ignatius knew this was no mere visualisation technique. As he writes in Spiritual Exercises §2:

“It is not much knowledge that fills and satisfies the soul, but the intimate understanding and relish of the truth.”

In imaginative contemplation, “intimate understanding” happens when the Spirit takes our sensory imagining and fills it with divine presence. Christ is not a character in a storybook; He is the living Lord who addresses us now, using the landscape of our mind as His meeting ground.

For Ignatius, imagination wasn’t just a mental exercise. It was a holy place where the Spirit could meet us, speak to us, and draw us deeper into Christ’s life. Fill your inner world with the stories of grace, mercy, and truth, he would say, and your outer world will start to look different too.

This is why the erosion of our imagination in the digital age matters so much — because the space God can use to speak with us is the very space our screens are slowly crowding out.

How Simulation Stunts Imagination and Reality

Our brains have a network of regions — often called the default mode network or “imagination network” — that lights up when we construct mental images, remember the past, or imagine the future. It draws on the hippocampus (memory), the prefrontal cortex (planning, moral reasoning), and the parietal lobes (spatial awareness) to build “inner worlds” from incomplete information.

When we read a novel or hear half a story, this network works hard: we imagine faces, places, smells, and sounds that aren’t supplied for us. The effort strengthens neural connections, deepens memory traces, and trains the brain to link experience, meaning, and anticipation.

But high-definition simulations bypass this work. They give the brain everything: the exact look of the hero’s face, the colour of the sky, the tone of the music, the rhythm of the conversation. Your sensory cortex is flooded with finished data, leaving the imagination network mostly idle. Over time, this “low-use” state can weaken the brain’s ability to generate vivid inner imagery, much like an underused muscle atrophies.

The result? We become skilled at consuming other people’s worlds but clumsy at inhabiting God’s.

You know this if you’ve watched a truly scary scene in a film. Often it’s not when the monster appears, but when the floorboard creaks, the shadow flickers, the door slowly opens. The space left open is where your imagination rushes in, and what you imagine is usually worse than what the director could show.

That gap — the unseen—is vital to faith. Scripture tells us that “faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” A screen culture that leaves no unseen space trains us in the opposite habit.

Finished, hi-def worlds also change our expectations of real life. Real life has texture, imperfection, delay, and ambiguity. But when you are conditioned to the polished pacing of films, games, and curated feeds, ordinary reality feels disappointingly uncinematic. We grow impatient with the slow work of relationships, the quiet seasons of prayer, the unfiltered moments of beauty.

And here lies a deeper danger: these mediated worlds are not neutral. Every one of them carries values, longings, and visions of “the good life.” They catechise us — training our hearts and minds in the liturgy of consumerism. And with our imaginations weakened, we become passive to these scripts.

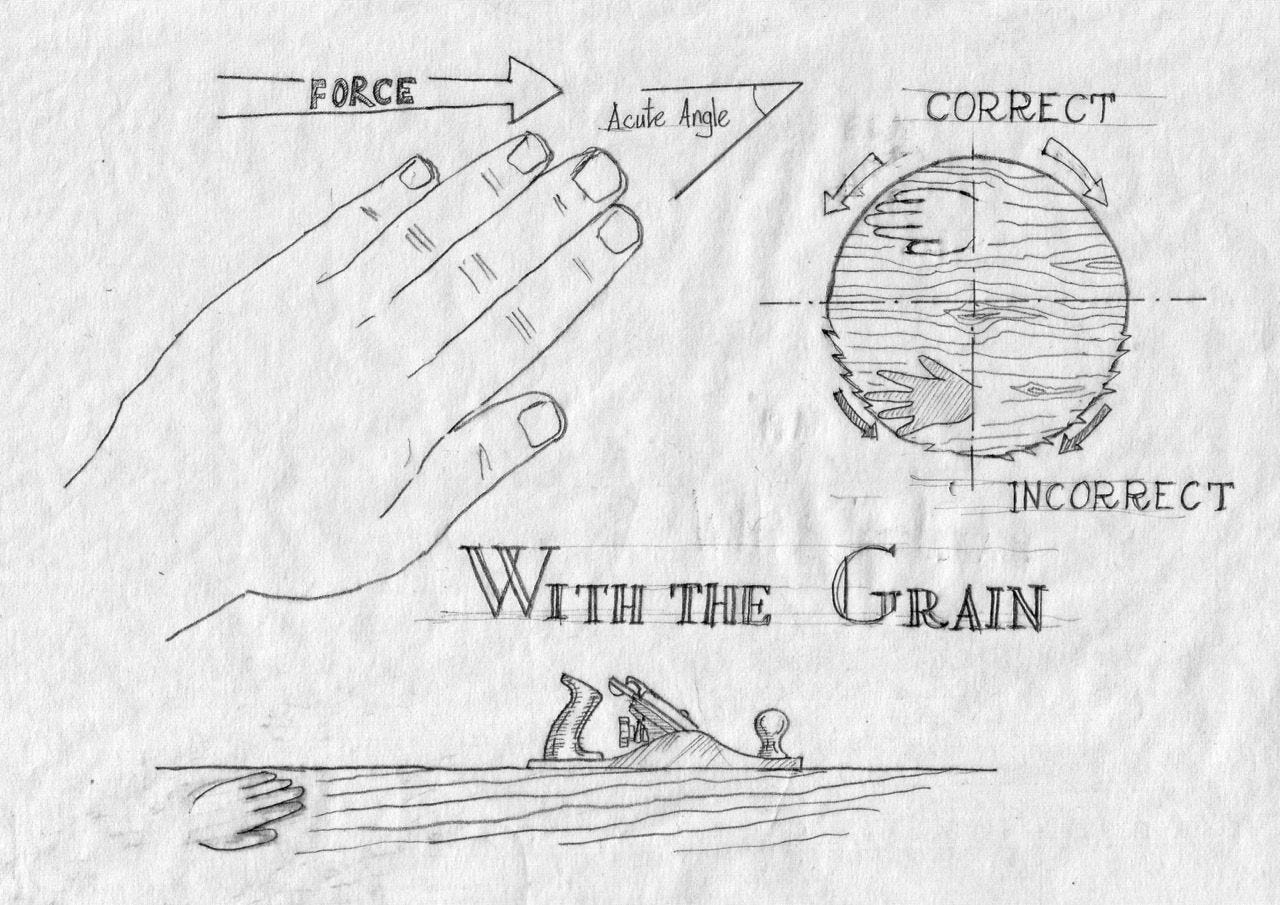

Imaginative Prayer: Working with the grain

Ignatian imaginative prayer doesn’t fight against the way the human mind works — it works with the grain of it. God created us as narrative beings. Neurologically, we are wired to make sense of life through story and to inhabit those stories in our minds.

The brain’s default mode network — the same system that lights up when we daydream, recall memories, or imagine the future — is designed to take fragmentary experiences and weave them into coherent meaning. It doesn’t just store events; it arranges them into a narrative arc, deciding what matters and what doesn’t.

This is why we remember moments in scenes, not bullet points. It’s why our dreams are visual. It’s why, when you tell someone about your day, you instinctively set the scene before recounting the action. And it’s why God gave us the Scriptures not as an abstract list of propositions but as a library of stories — salvation history told through the lives of real people in real places.

The Spirit meets us with the grain of our story

When we enter the Gospels in Ignatian prayer, we are stepping into the very format God chose for revelation. The Spirit meets us in that space because it is His medium: the narrative of salvation, from creation to Christ to new creation.

As I noted in a previous article:

Desire and imagination are indeed the forces that determine what we choose and act around for the creation of our lives. The Spiritual Exercises are about becoming free by exploring what we desire, with our imagination, into a different self. One that is God-created instead of self-created.1

Here’s where recapitulation comes in — a word the early Church loved because it captures the scope of what God has done for us in Christ. In the Christ event — His life, death, resurrection, and ascension — Jesus takes the entire human story into Himself. He does not merely fix a broken part or offer a moral example; He gathers it all up. The first Adam’s failure and exile. Israel’s vocation and struggle to be God’s covenant people. The long ache of humanity’s wounds, sins, and estrangements. Even the tangled threads of our personal histories — the triumphs, the betrayals, the wasted years, and our unhealed pain.

The Church Fathers called this participation — sharing in the life of Christ here and now. As Athanasius wrote, “He became what we are that He might make us what He is.” In imaginative prayer, that participation is tangible: we stand in His presence, He speaks, we respond. And this encounter is as real as the sacraments, because the same Spirit who meets us at the Table meets us in the landscape of our redeemed imagination.

So we can pray in confidence: This is not pretending. This is presence.

Recapitulation is the ultimate realignment of our lives with the grain of God’s intent. To pray imaginatively, then, is to step into scenes where this reality is alive and unfolding — to see ourselves not as spectators of a sacred drama, but as participants whose lives are now woven into Christ’s.

Ignatian prayer makes this theological truth experiential and real to us:

We bring our own life into the moment — our fears into Gethsemane, our grief to the cross, our hopes to the resurrection morning.

The Spirit joins our personal “story threads” to Christ’s story, until His narrative arc becomes the shape of our lives.

In that union, healing happens. The old story is gathered into His, redeemed from the inside out, and returned to us renewed.

And our imaginations are developed; they come alive, as we come alive in Christ.

Imagination as Participation, not Pretence

Many modern Christians have been trained to distrust the imagination, fearing it might distort the “truth” of the Gospel. But when the imagination is sanctified, it does not compete with truth; it participates in it.

In fact, without imagination, truth remains a sterile abstraction.

In Ignatian prayer, the imagination doesn’t create a fantasy Jesus — it becomes the God-given faculty the Spirit uses to bring the real, risen Christ to us. We are not “pretending” to be at the Sea of Galilee or the empty tomb. We are allowing the Spirit to collapse the centuries, bringing our presence into His presence, our today into His eternal “now.” By the Spirit, it is as if I were there with Christ and Him with me.

I had such an experience when undertaking the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises:

A few years ago, in a time of prayer, in my mind's eye, I saw Jesus. He stood before me with his head jauntily cocked to one side. Winking at me, he asked a rhetorical question, his voice full of mirth, knowing my answer before I gave it.

'Follow me?'

My answer was a silent yes; no words were required; he already knew my answer.2

This was not mere fantasy, but an experience of the deepest reality of God in my life.

Why We Need This Now

Screen culture leaves us spectators. Certain forms of Christian cognition can leave us as mere analysts of the Gospel. But the Spiritual Exercises call us into the dust and sweat of the road, the breaking of the bread, the agony of the garden, and the joy of resurrection morning.

They reclaim the imagination for its true purpose: to mediate between what is unseen and seen, between God’s eternal life and our everyday reality. And in that space, the Spirit makes Christ real to us — here and now.

Or, as I wrote in another article:

“We are invited… to sit before God with his word, and… enter into salvific experiences of the risen Jesus, personally present right now in the Spirit to you and to us all.”

So this week, in place of the scroll and atrophy of your imagination, why not try some Ignatian prayer and compare the experience?3

Something to try

Pick a Gospel story where Jesus meets someone in need.

Enter the scene: what do you see, hear, smell, and feel?

Be there: where are you standing? What’s going on inside you?

Let Him speak: listen for His words to you.

Respond: speak to Him, then stay with Him.

The imagination is never neutral. It will either be colonised by something or claimed by Christ. The Spirit is ready to make it the latter.

See What is the Purpose of the Spiritual Exercises, Jason Swan Clark

Was that really you Lord, or just my imagination?, Jason Swan Clark

For a more detailed walk-through of how to practice Ignatian Imaginative Prayer, see https://thejesuitpost.org/2021/10/jesuit-101-ignatian-contemplation-encountering-god-through-our-imagination/

I've been asked to lead a 'reflective service' this coming Sunday evening. This morning, I thought I might well construct it around some Ignatian Bible reading. Tonight, I read your post (having saved it for when I had time to read it without hurrying) and the idea seems all the more important. Thank you.

This is quite helpful. Thank you, Jason!!